THE PERFECT STRANGER: A MODERN COMPOSER (CNTD.)

The co-operation with the Ensemble Intercontemporain worked well for both sides for the publicity aspect, but not for building up a good relationship. Some members had expected arranged pop music and doubted whether Zappa could write scores himself. The atmosphere changed to the bad when the ensemble found itself sweating on the compositions and Zappa demanded perfection, sending away musicians that weren't performing up to his standards. The European continental world of modern music during the previous century used to be full of intellectualism and leftism. It only survived on government subsidies. Flirting with communism was fashionable among European intellectuals during the seventies. Today this tendency is gone, with a remnant occurring in 2001, when Karl-Heinz Stockhausen was videotaped calling the September 11th attack a masterpiece of art.

1. The perfect stranger

The piece that Pierre Boulez originally commissioned and got the project going.

It follows directly upon the material on "The LSO Vol. I", stylistically and in orchestration, but also coming up

with some different approaches. For instance Zappa didn't include a drumset this time.

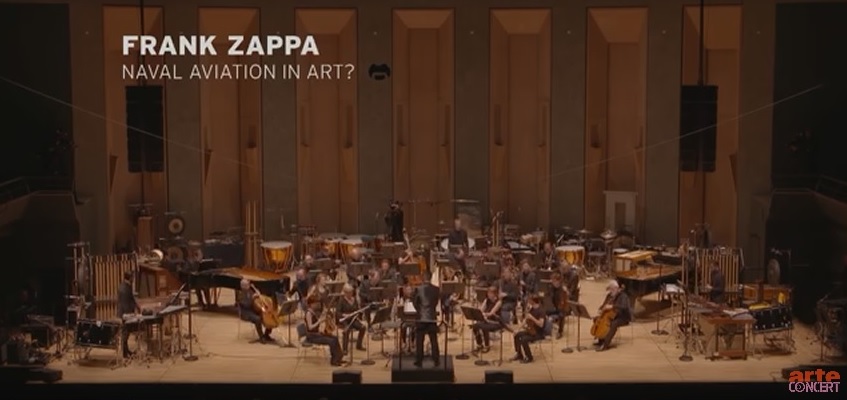

In October 2011 The Doelenensemble played some pieces from "The perfect stranger",

including the title track. To the left you can see them during their concert at The Doelen, a concert hall in

the city of Rotterdam, Holland. The scores are today only for rent for public performances. A flash file on Youtube

makes a transcription much easier, because one now has the opportunity to follow their conductor. The following is 1:18-1:40 from their

performance, that corresponds with 1:02-1:21 on the Boulez album (the time difference is due to an opening pause).

Again there are version differences, as happens more often in Zappa's output. Because I don't have

the original score, I can't tell what causes it. There might very well be different versions of the score itself,

because there are various examples of Zappa revising his compositions.

If this is not the case then either

during the Boulez recordings adaptations were made or during the Doelenensemble rehearsals. It's theoretically also possible that Zappa edited the tape

in his studio after it got recorded. The CD I have carries the edition number Rykodisc RCD 10542, referring to a master tape, approved by Zappa in 1993. In the Boulez version the irregular

groupings within a 9/8 meter may look awkward, but it's something Zappa could do, also for his rock band (see the second "Drowning witch"

example with the figure for "she could mutate insanely").

The piece that Pierre Boulez originally commissioned and got the project going.

It follows directly upon the material on "The LSO Vol. I", stylistically and in orchestration, but also coming up

with some different approaches. For instance Zappa didn't include a drumset this time.

In October 2011 The Doelenensemble played some pieces from "The perfect stranger",

including the title track. To the left you can see them during their concert at The Doelen, a concert hall in

the city of Rotterdam, Holland. The scores are today only for rent for public performances. A flash file on Youtube

makes a transcription much easier, because one now has the opportunity to follow their conductor. The following is 1:18-1:40 from their

performance, that corresponds with 1:02-1:21 on the Boulez album (the time difference is due to an opening pause).

Again there are version differences, as happens more often in Zappa's output. Because I don't have

the original score, I can't tell what causes it. There might very well be different versions of the score itself,

because there are various examples of Zappa revising his compositions.

If this is not the case then either

during the Boulez recordings adaptations were made or during the Doelenensemble rehearsals. It's theoretically also possible that Zappa edited the tape

in his studio after it got recorded. The CD I have carries the edition number Rykodisc RCD 10542, referring to a master tape, approved by Zappa in 1993. In the Boulez version the irregular

groupings within a 9/8 meter may look awkward, but it's something Zappa could do, also for his rock band (see the second "Drowning witch"

example with the figure for "she could mutate insanely").

The perfect stranger, 1:22-1:40 (Doelenensemble) (midi file).

The perfect stranger, 1:02-1:21 (Boulez conducts Zappa) (midi file).

The perfect stranger, fragment (transcription).

The differences to be heard in the Doelenensemble version are:

- Preliminary notes: 4:5 eight notes become a regular intro, lasting 3/4.

- Bar 1: the 4:5 eight notes become 4:3 quarter notes. The meter

of bar 1 thus becomes 5/4.

- Bar 3: the 5:4 eight notes become 4:3 quarter notes followed by a dotted eighth note. The first note

of the ninetuplet gets into the 4th beat followed by normal 16th notes. Bar 3 then lasts 6/4.

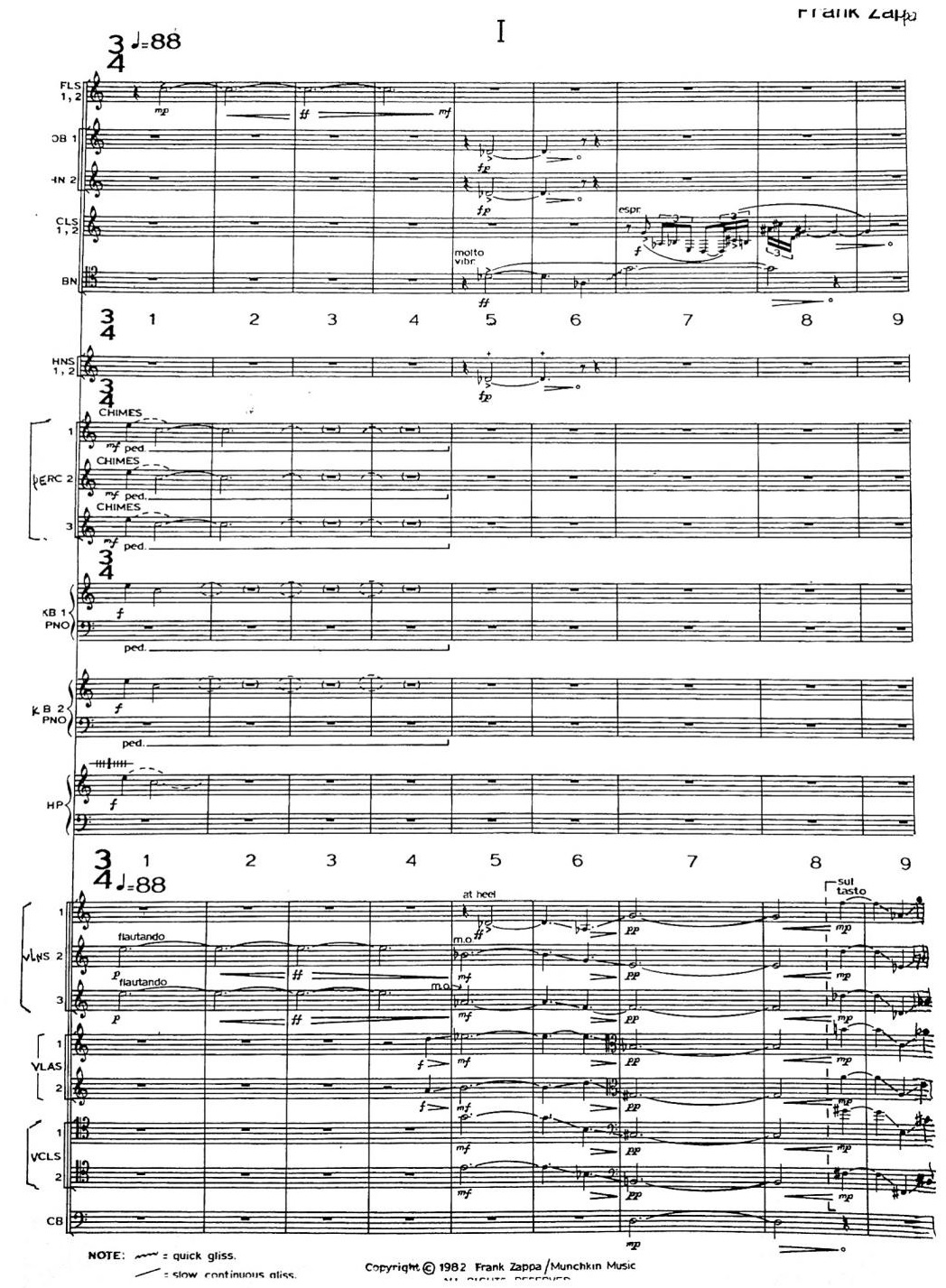

The picture you're getting is clear: "The perfect stranger" is an outspoken atonal composition with various

forms of irregular groupings. Everybody is playing the same rhythm, thus you're creating a series of chords made

up of three parts: the descant in the first two staffs, a part in the middle (staff 3) and a bass part (bottom staff).

With the original scores unavailable to the general public, reproduced sections in studies can be helpful. In this case

"The perfect stranger" gets ample attention in two academic studies. These are the ones by Martin Herraiz (H.) and Brett Clement

(Cl.). See the references in the left menu for the details. Their analyses deal with the thematic construction of these pieces, but

mostly with the formation of harmonies. An attempt is done to identify several chords as being part of a so-called chord bible, a set

of preferred chords Zappa appears to have used around this time for his orchestral works (as mentioned in the previous L.S.O. section,

otherwise see the 2009 study by Clement). Combined these two studies offer enough

examples from the original score to get a reasonable estimation of "The perfect stranger". Thus it can be seen that the score knows two movements.

On the Perfect stranger CD the transition, happening at 3:50, is not perceptible: there is no pause taken, or any clear change for that matter.

Strange, because the audible caesura at 10:14 (bar 213) apparently does not

coincide with a new movement.

The reproduced examples cover:

Movement 1

- Excerpts: bars 5-17, 43-46 and 48-51 (Cl.).

- Chords: bar 37 (Cl.).

- Lead melody, with chord indications: bars 52-62, 65, 71-77 and 79-85 (H.).

- Reduction: bars 79-85 (H.).

My first example from above can be found half way between bars 17 and 43.

Movement 2

- Excerpts: bars 1-8, 16-20, 21-25 and 56-60 (Cl.).

- Lead melody: bars 17-32, 48-70, 71-78, 199-222 and 234 (H.).

- Harmony, reduced: bars 48-77 and 215-217 (H.).

- Reduction: bars 221-226 (H.).

Brett for instance notices thematic variations over a distance, like I did in the L.S.O. section with "Mo 'n Herb's vacation". On page

229 of his study he describes what he calls the main theme from "The perfect stranger", a melody of 12 notes, first occurring during

bars 8 through 16 of movement I (not a 12-note serial string to avoid any confusion). These concern bars 8-17 (see below), his example 5.38a.

Further below on the same page he continues

with: "now consider Example 5.38b, the second statement of the theme in "The Perfect Stranger

I." Here, the melody appears in isomelic variation, with the first three pitches transposed by T2.". His example 5.38b are bars

43-46. Isomelism is a term he's using for a rhythmic variation, where the pitches of the melody are kept the same, or transposed only (the word isomelism is

academic Greek for "same melody").

T2 stands for a transposition with a major second.

On page 231 Brett continues with "[...] the fourth, and final, statement of the theme in "The

Perfect Stranger", occurring at m. 199 of "The Perfect Stranger II". This final statement initiates

a huge isomelic restatement of the previously discussed mm. 16–78, which plays out until the

close of the piece. Here, however, the theme is returned to its initial pitch level (beginning on

F, as in Example 5.38a)."

These examples seem to corroborate that there are version differences between the Boulez recording and the scores distributed today, including the score example from below, dated 1982.

The examples by Brett of bars 5-17 are reductions. The following can be noted as it comes to the opening:

- Bars 1-4: the sustained two "doorbell" notes: the perfect stranger, a door-to-door salesman, is ringing the doorbell (see the CD booklet).

- Bars 5: the 1982 score includes two chords:

a) On beat 1, sustained during beats 2-3: E-G-Ab-Bb-B-Eb (strings only).

b) On beat 2, sustained during beat 3: to this chord an accentuated Db gets added (violins 1 and wind instruments).

On the CD (Rykodisc RCD 10542) this became only one chord, which is also happening in Brett's example. Apart from this and the instrumentation, his example of bars 5-7

is identical to the 1982 score.

The first difference with the CD is that there are tempo changes needed to get it synchronous with the CD. For instance bars 5-6

last as long as bar 7, a bit puzzling. So either Zappa added large tempo changes or bars got contracted or skipped.

- Bar 6: the full chord from bar 5 gets sustained for half of bar 6, followed

by another wide chord for the second half: Ab-Bb-B-F-G-D-Eb (the Eb coming over from the previous chord, still sustained).

- Bar 7-8: bar 7 starts with a new sustained chord, B-C#-D-G#-Bb-E-F-G (the F coming over). On top of this a clarinet melody gets played.

There are little differences to be heard in this lead melody in bar 8.

- In bar 9 an A natural is played instead of an A flat in Brett's example. Otherwise it's hard to distinguish all individual notes. It sounds like some instruments are

fluctuating in the background, rather than playing single sustained notes.

Because of these differences it can't be taken for granted that all of the analyses by Martin and Brett

(based upon the score in their possesion) apply to the Boulez version as well. Both talk about the Boulez recording as if this is the identical piece.

The perfect stranger, opening (Boulez conducts Zappa) (midi file).

The perfect stranger I, bars 5-10 (Boulez conducts Zappa) (transcription).

The perfect stranger I, bars 5-17 and 43-46, plus The perfect stranger II, bars 199-212 (score)

Opening page of "The perfect stranger", as reproduced in "Zappa, L'un et le multiple", Presses universitaires de Rouen et du Havre, 2017.

Something you can also notice is the high degree of syncopism. Zappa willingly avoided any perception of steady rhythms within this piece, with downbeats only happening half of the time, something

which may explain why irritations grew during the recording sessions with the Ensemble Intercontemporain. Zappa's music requires a perfect understanding of timing, which, in case

of a larger group of musicians playing together, can be demanding without much rehearsing time.

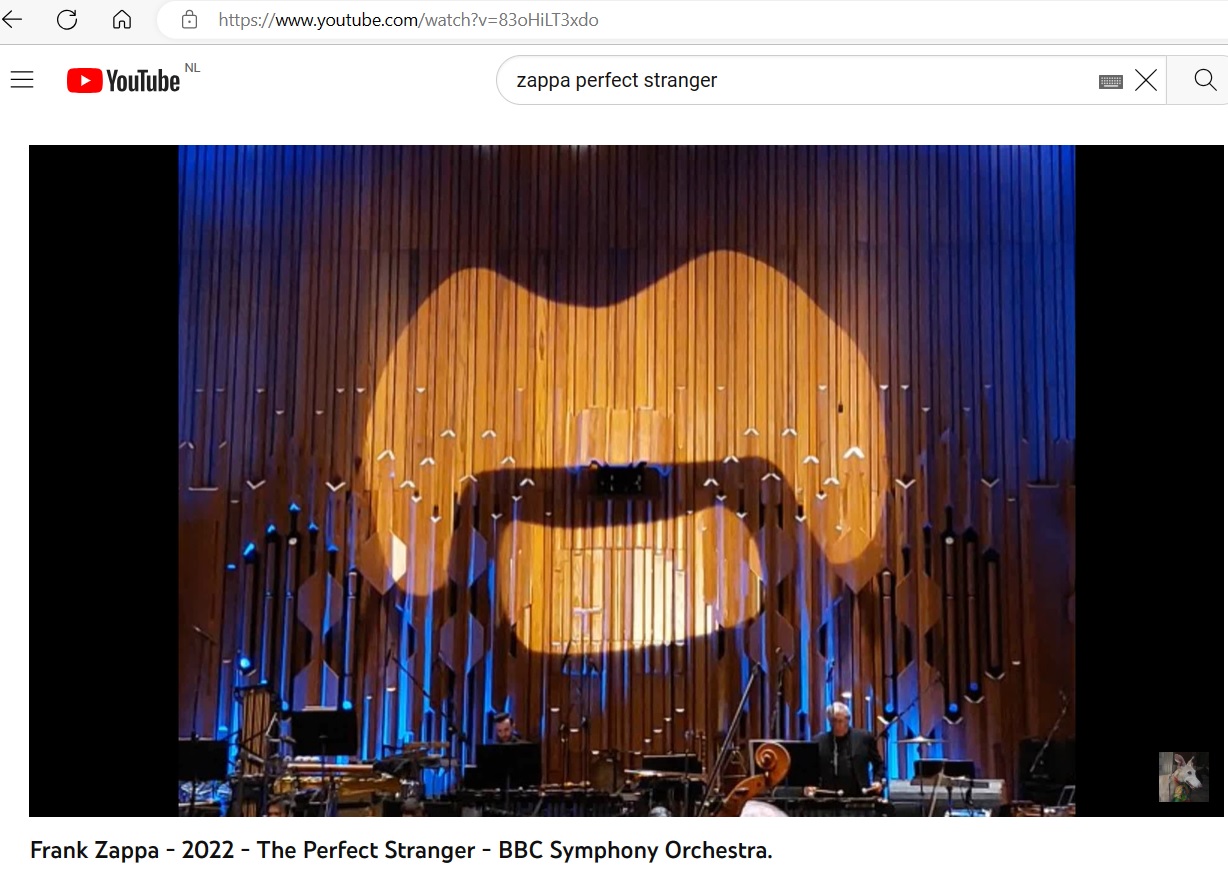

In 2022 the BBC Symphony Orchestra performed several pieces from the "L.S.O." and "Perfect stranger" albums, among others "Sad Jane", "Mo 'n Herb's vacation" and the title track

from "The perfect stranger" (above an image from as how you can find it on YouTube). Comparing examples from the Herraiz and Clement studies with the 1984 and 2022

recordings further points at the existence of version differences.

The perfect stranger I, bars 79-85, score version (midi file).

The perfect stranger I, bars 79-85, transcribed version (midi file).

The perfect stranger I, bars 79-85 (score/transcription).

The first midi file from above are bars 79-85 from Mvt. I, played as in the original score. Martin has not included the dynamics, possibly some parts should be played

at a piano or pianissimo volume, rather than the mechanical presentation of my midi file. But it's getting more likely that various parts got skipped altogether, which

was also done frequently during the "200 Motels" and "L.S.O." sessions. The second midi file is based upon a transcription of the same section. I may be not hearing some

notes, but various notes were left out and a few added. The difference is remarkable and makes this passage much less dissonant. When you're listening to the BBC Symphony

Orchestra version from 2022, it appears to go like the 1984 CD. This suggests that the score may have got revised during the sessions with the Ensemble Intercontemporain

and that this revised version is the currently available form.

The perfect stranger II, bars 1-8 (midi file).

The perfect stranger II, bars 1-8 (score/transcription).

The last bar from the previous example is the last bar from movement I. Its chord gets briefly sustained, moving over to the first chord of the second

movement in a glissando manner. The first eight bars of this movement are present in the Clement study. Brett calls it an interlude, containing six

mostly octatonic chords, that are often played on top of each other in pairs, as shown above. On the 1984 CD recording this gets played as:

- First chord: Ab-Bb-B-C#-E-F-G-D, as density (minor second distances) 2-1-2-3-1-2-7.

Not all notes of this chord are brightly audible, probably some got skipped.

- Second chord: E-F-G-Ab-Bb-Cb-D-C#, 1-2-1-2-1-3-E(11).

Idem and now one note is audible an octave lower than in Brett's example, a D by the oboe (staff 2 of my example).

- Third chord: D-F-G-Ab-E-A#-B, (12+)3-2-1-8-6-1.

The notes from this chord come up and go in different manners from beat four

of bar 1 through beat 1 of bar 4. Here the dynamics are getting important, not properly represented in my midi file.

- Fourth chord: C#-D-E-F-Ab-A#-B-G, 1-2-1-3-2-1-8.

The Ensemble Intercontemporain did have a string section of eight players, but as a chord

this chord is hardly audible. Better recognizable are individual notes as the G from staff 8 from bar 4 of my example.

- Fifth chord: G-Ab-B-C#-D-E-F-Bb, 1-3-2-1-2-1-5.

This chord for the celesta got replaced by arpeggios by the harp.

- Sixth chord: E-G#-A#-B-C#-D-G-F, (12+)4-2-1-2-1-5-T(10).

Same as for the fourth chord.

Brett mentions where his example can be heard on the CD, adding that the notes of these chords

weren't played all at once, but he makes no issue of adaptations. His analysis on pages 232-3 of his 2009 study goes as:

"For example, consider the excerpt provided in Example 5.41. This passage occurs

at the beginning of "The Perfect Stranger II" as a self-contained interlude, and is soon followed

by one of the thematic statements. In total, six separate eight-note octatonic densities are stated

in the interlude, each by one of four instrumental groups: woodwinds, brass, celesta, or strings.

[Note 72: The third density of the excerpt, D[3-2-1-8-6-1-14], requires the high C# of the preceding density D[1-2-

1-2-1-3-E] to complete itself.]

Though none of the densities are attacked simultaneously, most chords continued to sound well past the attack of the following chord.

Throughout most of the passage, in fact, at least two

chords are sounding simultaneously. Because superimposition is employed here, all

simultaneously sounding chords must be of the same octatonic scale. Further, because

superimposition is at work throughout the entire passage, all six of these chords must maintain

the same scale. Not surprisingly, this shared collection is OCT1,2, which, as already detailed,

plays a crucial role throughout the piece."

As I understand it OCT stands for a collection of 16 octatonic chords Brett considers safely identified as chord bible chords,

being a number of denstities build upon the notes of the following octatonic scale (upon C):

C-C#/Db-D#/Eb-E-F#-G-A-Bb. In the example above this scale is present upon C# as C#-D-E-F-G-Ab-A#/Bb-B,

which is indeed the collection of notes used by chords from the example above. Subscriptum 1,2 points

at which note can be present as root of a chord, step 1 (D) en step 2 (E). See example 5.29 from his

2009 study and the section about octatonic chords. The densities from the chords from the example above are also present in this table.

The perfect stranger II, bars 48-70 (score/transcr.) (midi file).

The perfect stranger II, bars 56-60 (score only) (midi file).

The perfect stranger II, bars 48-70 (score/transcr.).

The examples from the Herraiz study allow you to look at the score of mvt. II for a larger period, bars 48-70,

while the Clement study is giving the orchestration for bars 56-60. When comparing this to the 1984 CD once again

differences emerge:

- Most notes of the chords from the score are getting about inaudible on the album.

- The rhythm of bar 50 got adapted.

- The D natural from bar 54 is a Db on the album (this might be a writing error).

- The rhythm of bar 56 got adapted: 7:4 eighth notes got replaced by 7:6 eighth notes, which is causing the meter to change.

This last change is the type of more substantial rhythmic changes, also noted in the examples above. In the L.S.O. section I'm citing

Brett expressing his amazement about the fact that Zappa applied his chord bible to a relatively short period. Reality is even more resistant:

during the first recordings of the involved works he already didn't insist in many chord bible chords to be played literally like that. It's

a bizarre consequence of his "AAAFRNA" principle, that one can also notice during the "200 Motels" recordings and, to a lesser degree,

the "Yellow shark" recordings. During the mentioned 2022 performance, however, more of these chords is audible than in 1984.

I've included bars 56-60, with these chords better audible, as a midi file as well, so one can experience

the difference, as well as better understand the analysis by Brett of bars 56-60 from page 233 of his 2009 study.

It concerns the melody using the same octatonic pitch collection (below abbreviated as pc) as the chords:

"Another technique of superimposition employed by Zappa in "The Perfect Stranger"

represents a merging of the two previously discussed methods. This method involves the

melodic statement of chordal densities, whereby a melody's pitch-space realization is identical to

that of a Chord-Bible density. Two examples of this phenomenon are given in Example 5.42.

The first of these, Example 5.42a, occurs at the outset of the piece. Following two Minor Lydian

chords in mm. 5–6, the central eight-note octatonic D[9-2-7-2-6-1-2] arrives at m. 7 in the

accompaniment. Above this chord, a clarinet melody is superimposed that unfolds the eight-note

chord D[2-1-3-2-1-2-6]. Because this horizontalized chord is superimposed above the

accompaniment, both layers must utilize the same octatonic scale (once again OCT1,2). A similar

description applies to Example 5.42b, an excerpt from the lengthy hybrid section of "The Perfect

Stranger II." Compared to the remainder of this section, chordal successions are fairly rapid

here. Typically, a disparity in pc collection might occur in such situations. However, the

melody occurring in tandem with the chord successions unfolds the symmetrical eight-note D[2-4-2-1-2-4-2],

which utilizes the OCT1,2 scale. Therefore, the three different octatonic chords

found the accompaniment are expected follow suit [KS: probable writing errors for "found in" and "expected to"]. Interestingly, Zappa inserts the E-Lydian

chord D[E-5-T-4-1-2] within this process. This interpolation is made possible by the melodic

repetition of the pitches E-B-A# from mm. 57–59: pitches that do suggest the E-Lydian mode.

These repeated pitches serve a dual purpose: not only do they allow for the brief diatonic shift,

but the emphasized semitone B-A# of the motive also defines the axis of symmetry for the

octatonic density unfolded melodically."

While Brett's effort to show that the octatonic scale from above is very likely part of the chord bible is pursuasive,

more difficult to grasp is his how he starts his section about octatonic chords on page 214 of his 2009

study, stating that: "The final large category within the Chord Bible is comprised of chords based on the

familiar octatonic scale (0134679T). As with the Minor Lydian scale, the octatonic scale is not

found to any significant degree in Zappa's music prior to the time period under investigation.

In fact, it is quite possible that Zappa's interest in the octatonic scale may have come about as a

result of the Chord Bible itself. That is, wishing to expand the cardinalities of his chords beyond

seven, Zappa may have found the octatonic scale to be the logical choice of a scalar resource for

eight-note chords, given his propensity to avoid repeating pcs with chords."

That's unlikely for a guy who admired the work of Nicolas Slonimsky. See my Zoot allures page for Zappa and Slonimsky.

Anyway, Zappa's interest in chords larger as seven-note chords existed much longer. See my 200 Motels page at

"Touring can make you crazy" and "The pleated gazelle", as well as the coda from "Penis dimension"

from my Just another band from L.A. section, for a variety of examples of such larger chords.

2. Naval aviation in art? - Jeff and Don

A large sequence, moving motifs over a changing chord texture. As with more of Zappa's works it's a one-time only type of composition, adagio all through and

dealing intensely with harmonies. Quite uncharacteristic for Zappa.

The origins of "Naval aviation in art?" must lie before 1971, because elements of this composition

were used as background music for "200 Motels" (see below at "Jeff and Don").

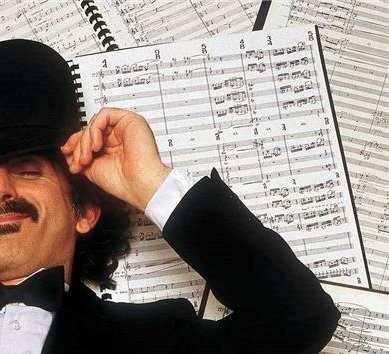

To the left right an outtake from a photo by Guido Harari with Zappa lying on top of his scores, around 1982.

A large sequence, moving motifs over a changing chord texture. As with more of Zappa's works it's a one-time only type of composition, adagio all through and

dealing intensely with harmonies. Quite uncharacteristic for Zappa.

The origins of "Naval aviation in art?" must lie before 1971, because elements of this composition

were used as background music for "200 Motels" (see below at "Jeff and Don").

To the left right an outtake from a photo by Guido Harari with Zappa lying on top of his scores, around 1982.

"Naval aviation in art?" is an exceptional work in Zappa's output, because it's specifically dealing with instrumentation all through this composition. The central element

are sustained notes, that every few bars change position via a string of (mostly) 32nd notes (staves 1-2 of the "Orchestral favorites" example and

and staves 6-7 of the "The perfect stranger" example). These notes are called the melodic notes in the tables below. It can be seen as a huge sequence.

The other parts hardly play melodic lines, but harmonize this sequence via single notes coming up and disappearing again. The wealth of atonal chords and sound combinations is amazing. When Zappa

wrote for orchestras, larger ensembles or jazz big bands, it always sounds thus natural as if he had been doing so all of his life. The actual number of instances that

he could work in this way is relatively little. His financial means grew through the years, but there's no real juvenile and mature Zappa. He could step into

things straight ahead.

Naval aviation in art? (Orchestral favorites), bars 1-7 (midi file).

Naval aviation in art? (The perfect stranger), bars 1-12 (midi file).

Naval aviation in art? (Orchestral favorites), bars 1-7 (notes).

Naval aviation in art? (The perfect stranger), bars 1-12 (notes).

According to Gail Zappa "Naval aviation in art?" stems from the "200 Motels" period, with the title taken over from

a magazine photo featuring navy employees in a specific line-up (liner notes from the "Greggery Peccary & other persuasions" CD by the Ensemble Modern).

It first appeared on "Orchestral favorites" and got recorded again for "The perfect stranger" in a much different version. The first thing that's directly

noticeable is the tempo difference. Bars 1-12 from above last 27 seconds on "Orchestral favorites" and 47 seconds on "The perfect stranger". Other

differences are numerous. "Orchestral favorites" begins with a pick-up bar with 32nd notes and a 16th note by the flutes (two flutes are used for the stereo field).

The 32 seconds

notes in bar 1 and 3 are by a single

violin, thus no clarinets, and played an octave higher than the viola on "The perfect stranger". The 32 seconds notes by the flutes are present again in bar 4 with no

comparable notes on "The perfect stranger". The harmony notes from bar 6 onwards are played by different

instruments, etcetera.

1979 version:

Bar number Melodic notes Harmony notes

- Bar 1 Ab, D#

- Bar 2 Ab, D#, B

- Bar 3 A, D#, B

- Bar 4 A, D#, E

- Bar 5 Ab, D#, E

- Bar 6 Ab, D#, B F, E, C#, D

- Bar 7 A, D#, B F, E, C#, G, C, D

1984 version:

Bar number Melodic notes Harmony notes

- Bar 1 Ab

- Bar 2 Ab, B, D#

- Bar 3 A, B, D#

- Bar 4 A, E, D#

- Bar 5 Ab, E, D#

- Bar 6 Ab, B, D# E, C#, D, C, F#

- Bar 7 A, B, D# F, E, C#, D, C, F#, G

- Bar 8 A, E, D# F, E, C#, D, C, F#, G

- Bar 9 Bb, E, D# F, C#, D

- Bar 10 Bb, D, E, C# F, G, C#, D, C

- Bar 11 B, D, E, C# F, G, Bb, C, B

- Bar 12 B, F, G, E A, G, C, B

Both versions begin calmly with three notes sounding for bars 1-5. From bar 6 onwards things are getting dense. The number of notes sounding

in combination varies between 6 and 10. In bar 7 from the 1984 version you're approaching the whole chromatic scale being played at once. It is

to be noted that Zappa little doubles the parts. Most instruments play their own notes. The permanently changing instrumentation, combined with the extensive use of dynamics,

makes that the composition remains transparent.

This piece gets dealt with extensively in the Martin Harraiz study, pages 211-227 (see the literature section). It begins with noting that

this piece is indeed exceptional in Zappa's output:

""Naval aviation in art" is an atypical work of Zappa. By this we mean that most of the

more or less general principles observed thus far are not present in this work: there is no particular 'melodic line',

nor are the striking rhythms present, that are often speech influenced and dense. It not only contradicts

his compositions for orchestras but for virtually any medium." So Martin doesn't interpret it as a sequence as I did above, but

also takes the notes I indicated as melodic as to be seen as just sustained notes. This study is in Portuguese, so it's translated

here with some liberty.

Frank Zappa tribute 2018: Ensemble Intercontemporain @ Philharmonie de Paris – ARTE Concert (as posted on YouTube).

Next the origins of this work and its different versions get commented upon, starting with: "Like most pieces of Zappa, it's

difficult to pinpoint the exact date when this work was composed: its first version

is best known as a recording from 1975 (included in Orchestral favorites album, released in 1979), but could already

be heard, much larger in instrumentation, as background music in a dialogue in the movie 200 Motels (1971). A catalogue of

the 1990s by the publisher Boosey & Hawkes brings information about a version of the piece for large orchestra,

probably the same that was used in the film (composed in the late 1960s, therefore, but already carrying

the final title)."

The analysis in the Herraiz study begins with

the initial bars from "The perfect stranger" (as presented above):

"The main elements that go to constitute the entire piece are presented already in this initial fragment. Its texture

can be schematically described as consisting of three layers. The third layer, which begins to act only

in bar 6, consists basically of long notes, sustained, generally

by several measures, whose points of entry and exit not follow any apparent pattern. The first two

layers however (which correspond respectively with staffs 8-9 and staffs 6-7, overlapping

homophonically, represented in this excerpt by starting with two clarinets and two violas), behave

clearly more regular and 'predictable'." The first two layers are then the ones I called "melodic" and the third layer are my harmony notes.

Above a 2018 screenshot with the Ensemble Intercontemporain.

As indicated in the http://globalia.net/donlope/fz site there's a section from "Naval aviation in art?" audible in the movie version

of "200 Motels", the conversation part between Rance Muhammitz and Jimmy Carl Black, that follows upon "Lonesome cowboy Burt". Zappa's

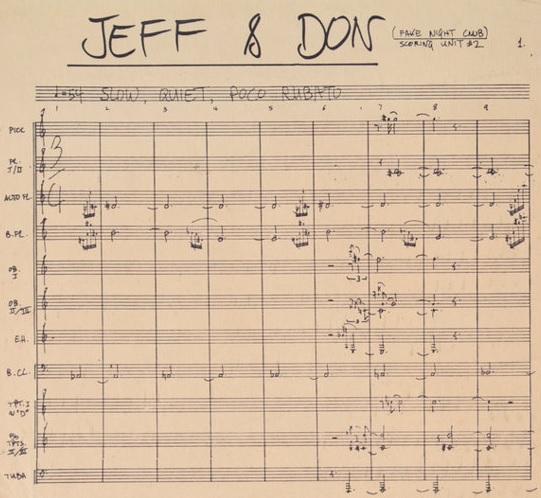

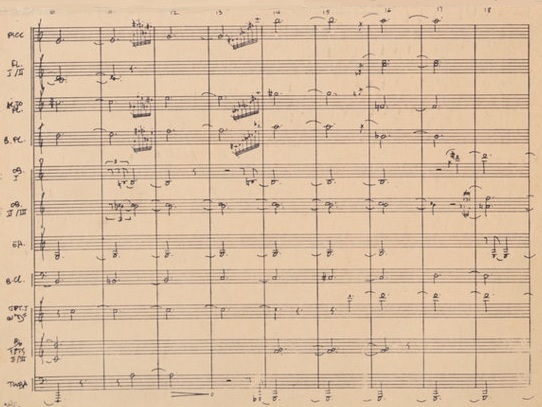

original handwritten score for "200 Motels" calls the corresponding scene "Jeff and Don", according to the sample below intended

to be played in a fake night club as scoring unit #2 (much of the script couldn't actually get filmed as planned).

In 2021 the ZFT released "200 Motels, 50th anniversary edition", showing that a full recording of this title from 1971 exists.

So Zappa decided not to use it in full at that time for the album or movie, nor was this piece part of "200 Motels, the suites".

Opening page of "Jeff and Don". Part of the "200 Motels scores" as auctioned at Heritage Auctions (2019).

Jeff and Don, bars 1-18 (midi file).

When you compare this score with the two examples from above, it turns out that in 1984 Zappa returned to the original score and that the 1975 version

is a revised version. Bars 1-12 are present in both examples, with the differences being marginal. E.g. the F by the tuba enters in bar

6 in "Jeff and Don", while it first appears in bar 7 in the 1984 score. Another difference is the fact that all the fast notes strings, that

precede the chord changes, were notated as grace notes in the original score. In the 1984 score they've become 32nd notes. More doable and more

effective, I think, if you want the hear the harmonies they form accurately performed.

Because Zappa notated metronome numbers on his scores, the intended duration of the example above can be calculated. 54 quarter notes per minute on this

occasion. 18 bars in 3/4 is equal to 54 quarter notes, so it lasts a minute, indeed slow.

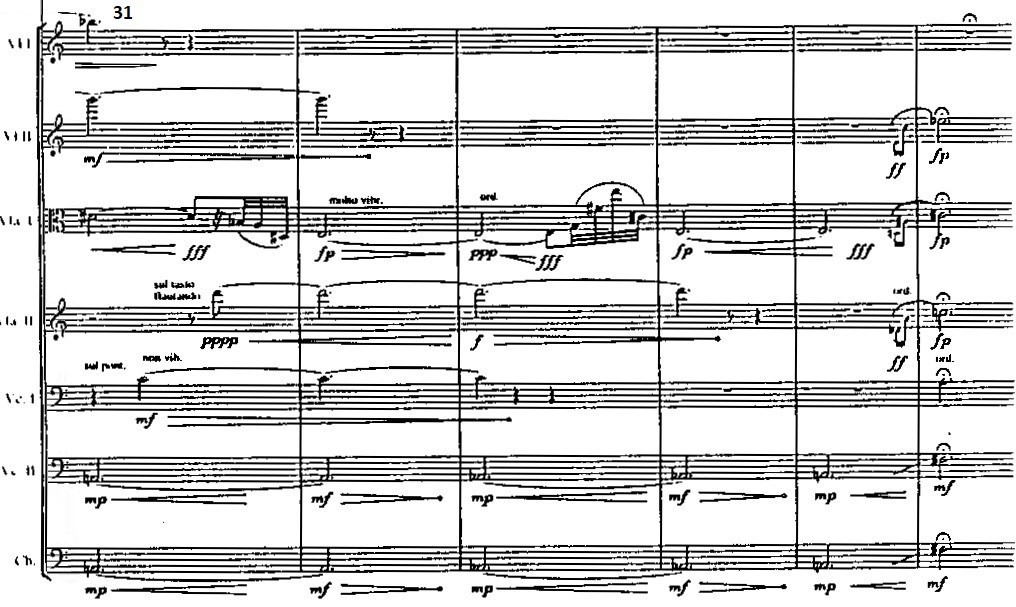

String section of bars 31-6 of "Naval aviation in art?" from the arrangement by Ali. N. Askin for the Ensemble Modern.

Another thing one can notice is that in 1971 at first no dynamics for this piece had been notated. Of the "Orchestral favorites" version I don't have samples

from the original score, but they are clearly present on the album, for which reason I indicated them in the example from above too.

They are also present in the reductions of the 1984 score in the Herraiz study, as well as the arrangement of this piece by Ali. N. Askin for

the Ensemble Modern (used for their "Greggery Peccary and other persuasions" CD from 2003). These dymanics are getting attention in Daniel Schröder's book

Frank Zappa - the composer, comparing them with Edgar Varèse's way of applying them in "Ionisation". He notes: "In Varèse's composition "Ionisation", the flexible shaping

of the depth of space proves to be an important structural property: as quiet sounds are felt by the listener as being further away than loud ones, dynamic prescriptions serve to

create a certain special depth [...]. Continuous dynamic movements can be found next to abrupt interchanges by way of fortissimo-piano-leaps [...]." "

And: "With "Naval aviation in art?", Zappa follows the same principle: the musical bodies of the trombone, the second cello and double bass go backwards and forwards

between mp and mf, whilst scanning the measurements of the spatial centre, the five-tone theme phase and its derivatives race from one dynamic extreme (fortissimo) to

the other (pianissimo), and thus huge distances in the shortest possible time within a considerably larger radius [...]. Throughout the entire piece, there is no image

created of a two-dimensional space within any single bar, as there is always a dynamic scaling both in the foreground as well as the background which is determined

by overlapping crescendos and diminuendos."

3. The girl in the magnesium dress

In the Guitar Player special issue Zappa! of 1992, Zappa explained the origins of "The girl in the magnesium dress":

"The piece was made from Synclavier digital dust ... [explains the existence of this dust as

G numbers, inaudible musical parameter data]. So

we converted this dust into something I could then edit for pitch, and the dust

indicated a rhythm. So what I did was take the rhythm of the dust and impose

pitch data on the dust and thereby move the inaudible G number into the world

of audibility with a pitch name on it".

Originally the piece went directly from the synclavier onto the tapes for the album. Later on the scores

were printed, reworked upon and orchestrated. In 1993 the Ensemble Modern opted for inclusion of the piece

for their concert program. The piece moves around between relative ease and, if you ask me, complete irregularity.

Zappa prescribes a constant high tempo. Bars 48 and 97 below are two opposite sides of the piece.

The girl in the magnesium dress, bar 48 (1993 CD: 1:55 till 1:58) (midi file).

The girl in the magnesium dress, bar 97 (1993 CD: 3:56 till 3:59) (midi file).

The girl in the magnesium dress, bars 48 and 97 (notes)

Bar 48 is relaxed, as good as following a scale. The E first jumps with octaves and then the E chord is formed.

Octave jumps and repeating notes return frequently in the score.

Bar 97 at the end of the piece is the opposite, a total frenzy, deliberately irregular. Zappa thought of

the piece as unfit for human performance, but the Ensemble Modern preferred to proceed. To make it

performable changes were made during rehearsals, in bar 97 for instance notes were skipped.

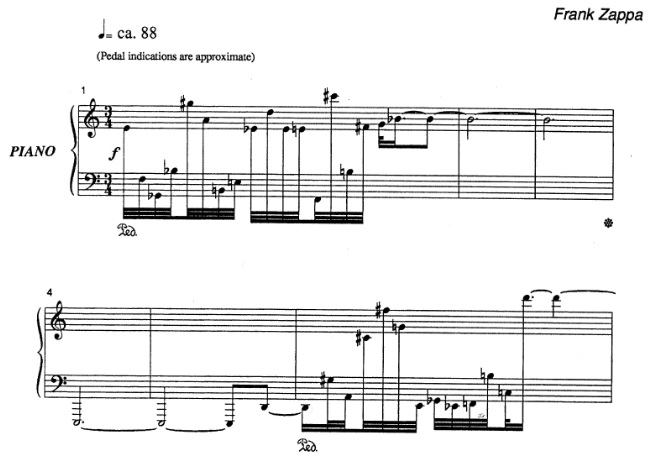

Bars 1-7 from the piano part of The girl in the magnesium dress as reproduced in Zappa!, page 66.

4. Outside now again

On side two of the original vinyl album the accent shifted towards the synclavier. The CD (Rykodisc RCD 10542) has the following order of tracks different from the 1984 album,

having for instance "Dupree's paradise" as track 4. Here I'm following the album.

For "Outside now again" Zappa typed in an improvisation over one of his favorite vamps. The melody goes much as the original "Outside now" guitar solo, transcibed by Steve Vai,

though there are differences.

- There are no dynamics per note, the dynamics are here achieved via doubling parts

in different staves.

- Various details have been adapted. Regarding the example below:

bar 1, beats 1-2: Eb-E as a glissando from the guitar book has become D-E.

bar 2, beat 2: B natural-E as a chord has become C-E without a glissando.

bar 3, beat 5: E followed by D as a grace note has become E as an eight note plus B as a 16th note within a triplet.

bar 3, beat 6 through bar 4, halfway beat 3: here the Guitar book prescribes a 6:7 figure going over a bar, also containing two triplets

within this tuplet. There are also two grace notes involved. On "Outside now again" this figure gets played like in the example below,

with the first grace note lasting longer as the second, the first more as a 32th note. I'm not positive about the exact notation.

bar 4: the final note from the quintuplet is played as a G instead of G quartertone sharp.

bar 5, beat 5: instead of a triplet with an A quartertone sharp as grace note in it, this figure gets played as a quintuplet with an A natural

instead of A quartertone sharp, lasting a 16th note within this quintuplet.

bar 6, beat 4: the lower additional G from the Guitar book gets skipped.

bar 6, beat 5: the grace-notes-chord B-D becomes more like a triplet 16th-notes-chord at the end of the previous beat.

The B natural-C# chord from the 5th beat has become C-E.

bar 7, beat 1: C followed by Eb has become C followed by F.

- The tempo is much slower.

- The sound of the melody as well as the overall sound is much different.

The combination of these factors causes "Outside now again" to sound as a new composition, rather than as a re-arrangement of the "Outside now" solo.

Guitar effects have been eliminated instead of attempts to simulate them digitally. Notable is the intentional removal of altered notes. It makes the example below

100% purely diatonic, which is definitely not the case during "Outside now" or Zappa's guitar solos in general.

Up to the 5th pdf version of this study I questioned if the synclavier (around 1984) could already support irregular

groupings as Steve Vai used them. After relistining I think it could, at least the quintuplet going over a bar from bars 2-3 (with a triplet within this quintuplet)

is executed without problems.

The notes from "Outside now again" can be found in the Frank Zappa guitar book,

pages 243-249, containing the guitar solo from "Joe's garage" (3:19-5:49). The example below corresponds with the first seven bars

from page 246. In total:

- 0:00-0:20 = page 243.

- 0:20-0:53 = page 244.

- 0:53-1:26 = page 245.

- 1:26-1:59 = page 246.

- 1:59-2:32 = page 247.

- 2:32-3:05 = page 248.

- 3:05-3:40 = page 249 till the penultimate bar at the point where Steve Vai marks "fade out".

- 3:40-4:06 = outtake from page 249. The melody from bars 7-9 from page 249 gets repeated, starting at beat 2 from bar 7. Beat 2 of bar 9 is also the point where the melody fades out,

so the composition can continue perfectly like this following the vamp.

Outside now again, 1:26 till 1:49 (midi file).

Outside now again, 1:26 till 1:49 (transcription).

See the "Outside now, 1979 solo" example from this study, as included in the Joe's garage section, for the original

guitar solo bars of the example above. On "Joe's garage" it lasts 17 seconds compared to the 23 seconds above.

Eventually the "Outside now" vamp

became used for five different solos. Compared to the "Joe's garage" version of "Outside now",

it's notable that the Bb-C alternation in the

bass isn't present. It makes it difficult for this version to determine what the keynote is. It's kind of floating. In his

response to me, Brett Clement calls it D Aeolian. If you have to pick a tonic, the sustained D is indeed the only option.

5. Love story

"Love story" is a short and energetic synclavier composition.

In the CD booklet Zappa describes the seven pieces from "The perfect stranger" as dance pieces, each with a story and built-in sound effects.

Sometimes recognizable but mostly absurd. In this case this piece would represent "an elderly Republican couple attempting sex while break-dancing".

Love story, 0:33-0:38 (midi file).

Love story, 0:33-0:38 (transcription).

The example above is a fragment of six seconds from this piece. As in many of Zappa's synclavier works, it's virtually impossible

to derive the meters from listening to the CD when there are no clear downbeats. The meter notation in the example is a notational choice only.

Bars 1 and 3 are brief hocketing melodies. Bar 2 contains a sequence of chords, that you're getting from combining the notes from the different staves.

It's difficult to exactly hear each note involved with certainty, so I can't get into details. What you can hear for sure is that it is atonal, often dissonant,

and that the intervals between the notes of the chords keep varying.

Pierre Boulez has followed a triple career in music. He is best known as conductor of

the modern classics from Wagner onwards. Secondly he was the driving force behind the Paris IRCAM institute for exploring

modern music, to which the Ensemble Intercontemporain belonged. Thirdly he is a composer himself. Zappa for instance was

well familiar with Boulez' composition "Le marteau sans maître" (photo downloaded, source unknown). He and Zappa would meet

more often, but till his death he preferred not to comment on the quality of Zappa's music. The tensions during the recording sessions

apparently had taken their toll. Otherwise this attitude is peculiar compared to what's happening on the album. Still you can find

reviews by people who can't accept the idea that a rock star could ever reach the level of their admired serious modern composers.

Pierre Boulez has followed a triple career in music. He is best known as conductor of

the modern classics from Wagner onwards. Secondly he was the driving force behind the Paris IRCAM institute for exploring

modern music, to which the Ensemble Intercontemporain belonged. Thirdly he is a composer himself. Zappa for instance was

well familiar with Boulez' composition "Le marteau sans maître" (photo downloaded, source unknown). He and Zappa would meet

more often, but till his death he preferred not to comment on the quality of Zappa's music. The tensions during the recording sessions

apparently had taken their toll. Otherwise this attitude is peculiar compared to what's happening on the album. Still you can find

reviews by people who can't accept the idea that a rock star could ever reach the level of their admired serious modern composers.

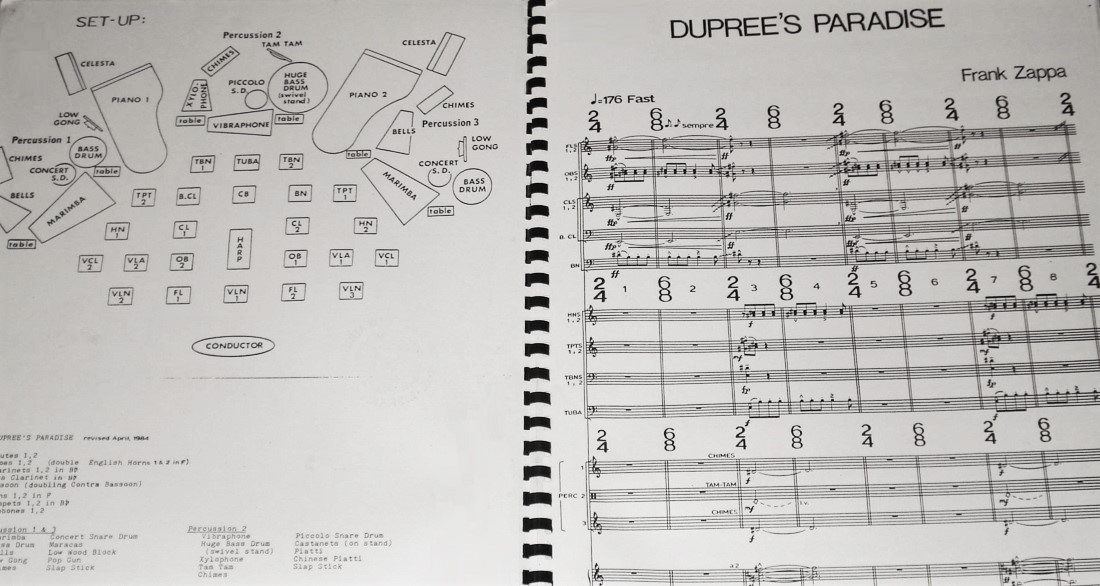

6. Dupree's paradise (1984)

The theme from the piece was first used in the seventies to set off soloing of the

group members. Here it has become an elaborate composition.

"Dupree's paradise" today exists in three quite different versions in Zappa's catalogue. The theme was first used for the 1973-4 tours

to introduce a large experimental improvisation block for the group members. See the YCDTOSA II section for a detailed description of this

"Dupree's paradise" (1974) performance. The 1984

execution only overlaps with the 1974 score for what I call phrases 1 and 2 in that section.

In 1988 it returned for incorporating a

trumpet solo over a vamp, followed by synclavier-rock band "jazz noise". In the version presented to the Ensemble Intercontemporain it's an 8 minutes piece

composed all through without any improvisation. An exciting masterpiece mixing diatonic and atonal material as presented

in the following two examples.

Dupree's paradise, opening bars 5-13 (midi file).

Dupree's paradise, bars 167-184 (3:45 till 4:11) (midi file).

Dupree's paradise, bars 5-13 (notes).

Dupree's paradise, bars 167-184 (notes).

The first contains bars from the opening with varying meters. It's played over E pedal

and follows the E Lydian scale.

The other stems from the middle section with two pianos playing in straight 3/4 over a bass counterpoint line. Here it's

all atonal. The movement is a sort of chromatic dance in a waltz meter, full of second intervals where the larger intervals serve

to keep repositioning the tiny seconds phrases.

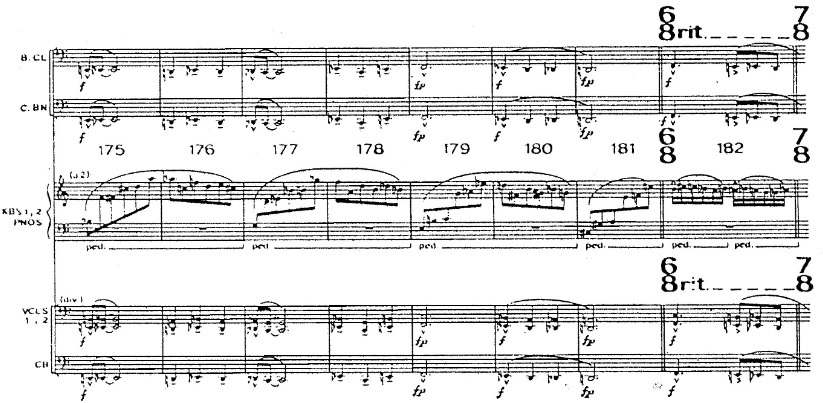

Bars 175-182 from Dupree's paradise as reproduced in the Ludwig study (L.).

Dupree's paradise, bars 131-135 (midi file).

Dupree's paradise, bars 131-135 (notes).

Examples from the original score can also be found in Brett Clement's "An introduction to Frank Zappa's Chord Bible" article (Cl.), like this last one with bars 131-5.

As indicated by Brett it gets played between 3:02 and 3:10 on the CD. See the L.S.O.

section for a paragraph about this chord bible and the left menu of this site, the Lydian theory page. These examples are used to examine the chords

applied in them. In bar 131, beats 1-2, you can find the following vertical cross sections (bottom up, the numbers being minor second distances):

- Beat 1: B-C#-F-F#-D-A-G#, 2-4-1-8-7-11.

- Beat 2, tick 1: E-B-C-D-F-G-G#, 7-1-2-3-2-1.

- Beat 2, tick 2: A-B-C-D-E-F-G#, 2-1-2-2-1-3.

Etc. The more often such a chord occurs in this title and other titles from this period, the more likely it gets such a chord might have belonged to the chord bible.

As also mentioned in the L.S.O. section regarding the opening bars of "Mo 'n Herb's vacation", it can occasionally happen that such combinations are diatonic, the third chord being the A minor scale, the variant

with a major 7th. The environment here is of course atonal. As also mentioned at "Pedro's dowry", Zappa's orchestral writing style is often mixed. The instruments play very brief melodies/motifs/single notes, sometimes

coinciding, more often hocketing, with their directions being the same or opposite. Since in this case the overall rhythm of all parts is similar, the ultimate effect is that these bars sound

as a chord progression.

Two more pages from the score are reproduced in Jonathan Bernard's article "The musical world(s?) of Frank Zappa" (B.).

In total you can find the score of the following bars in full in the mentioned writings:

- Bars 1-33: L.

- Bars 35-40: Cl.

- Bars 107-110: Cl.

- Bars 131-135: Cl.

- Bars 151-182: L.

- Bars 196-200: Cl.

- Bars 269-283: B.

Opening pages from the score. Photo downloaded from the net, cleaned up a little by me by removing stains etc.

7. Jonestown

Right after Zappa obtained a synclavier, he started using it for both note entry and the construction of sound collages. "Jonestown" is an early

example of a mixture of these methods, described by Zappa himself as an ugly dance evoking the essential nature of all religions. Jonestown was the

community of the Peoples Temple in Guyana, led by Jim Jones. If you're not familiar with what happened there, look it up, it became world news in 1978.

Jonestown, fragment (midi file).

Jonestown, fragment (transcription).

The example above can be heard between 2:16-2:30. Directly from CD a meter can't be detected with certainty. The dashed "4/4" lines are only there for readability.

Throughout this piece you can hear varying sustained notes, coming up and disappearing again, forming all sorts of harmonies.

"Bar" 1 from the example begins with C-Ab-E-B as a sustained chord. In bar 2 this chord moves over to B-C, while in bar 4 other notes are getting into the picture.

Staves 7-8 represent a longer melodic line. Staff 5 from bar 4 contains a shorter motif. There are also metallic instruments playing flurry melodies, during these

bars faintly in the background with hardly discernable notes. Not included in this example are instances of the various blast-like percussion beats, turning up frequently

during this piece.

These sound collages became ever more elaborate and eventually a form of art by themselves on "Civilization phaze III" and "Dance me this".

As I'm describing in the Baby snakes and Civilization phaze III sections, it's difficult to approach sound collages in the shape of sheet music in a normal way. Theoretically

it can be done, but I doubt how much wiser you might be getting from it. The problem lies in sounds, that aren't constant, and the improvised duration lengths of notes.

See for instance the shifting sounds of only three bars from "Basement music #2", that

I've tried visualize in the Baby snakes section. The meters and rhythms of collages are or can be chosen at will, so on paper they can be only approached

and they will look weird when you want to obtain some degree of accuracy.