ZOOT ALLURES: HARMONIES - PREFERRED AND UNSTABLE CHORDS?

With his 1976 "Zoot allures" album, Zappa delivered a rock 'n roll album, exaggerating the roughness that's supposed to

come along with it by posing as some sort of a creep on the album cover (photos by Gary Heery). The lyrics show the development of Zappa's sense of humour.

Provocative as they may be, they can also make you laugh by the eloquence Zappa is uttering himself with. Sentences describing the evil prince in "The torture never stops" can be very poetical, including rhyme, like "he's the best of course of all the worst, some wrong been done, he done it first" (the song is about the (religious) idea of punishing sinners, only revealed at the end). It becomes offensiveness with a smile.

"Zoot allures" is a good album to listen to for the use of regular chord progressions.

With his 1976 "Zoot allures" album, Zappa delivered a rock 'n roll album, exaggerating the roughness that's supposed to

come along with it by posing as some sort of a creep on the album cover (photos by Gary Heery). The lyrics show the development of Zappa's sense of humour.

Provocative as they may be, they can also make you laugh by the eloquence Zappa is uttering himself with. Sentences describing the evil prince in "The torture never stops" can be very poetical, including rhyme, like "he's the best of course of all the worst, some wrong been done, he done it first" (the song is about the (religious) idea of punishing sinners, only revealed at the end). It becomes offensiveness with a smile.

"Zoot allures" is a good album to listen to for the use of regular chord progressions.

HARMONIES (BRIEF OVERVIEW)

As in the case of rhythms, it's

undoable to present some sort of overview of the harmonies Zappa is using because he would play chords in any way he pleased.

The following mentions just some examples of certain directions he can take, ranging from the easiest progressions

to the most varied ones. Obviously anything in between will turn up as well. You would have to look through a larger

number of individual examples in this study to get a better picture.

Conventional chord progressions:

Conventional is here seen as a series

of 5th and 7th chords. In various examples the progressions you can encounter are mentioned in the comment, mostly

in Roman numbers, sometimes in rock terms.

- "Doreen", "Joe's garage": songs that are built around I-IV-V, one of the most common progressions. This can be seen

as sheer conventionalism.

- "Cheap thrills", "No, no, no": songs that make use of easy repeated progressions, in this case I-IV-I 7th-IV-I.

- "You are what you is": a song built over two alternating chords.

- "I ain't got no heart", "You're probably wondering why I'm here", "Jelly roll gum drop", "Bwana dick" etc.: larger

progressions, often with modulations. This applies to a large part of the examples in this study.

- "Run home, slow" movie sample #4, "Toad of the short forest", "America drinks", "It's from Kansas" etc.: things can get more and more complex till you get at

songs where Zappa keeps changing the scales about all the time.

Unconventional diatonic chord progressions (9th chords and bigger ones):

- "It must be a camel", "Little umbrellas": dense and complex harmonies, achieved by constructing a song

by recording it in layers.

- "Twenty small cigars" opening bars, "RDNZL", "Big swifty" piano part: other examples with larger chords.

- "five-five-FIVE": a sequence of 9th chords, led through various scales.

- "Regyptian strut", first example bars 5-7: an example where Zappa harmonizes the same melody in different ways,

using dissonants.

Unconventional diatonic chord formations via series of notes:

- "Dwarf nebula", "Music for low budget orchestra", "Friendly little finger" opening bars,

"Sleep dirt" accompanying chords, "Punky's whips" 33/32 bar, "Put a motor in yourself" etc.: various forms

of 9th and 11th chords.

- "Orange county": both conventional and unconventional chords. In his guitar solos and many composed melodies you can see a total harmonic freedom.

Cells with thirds, 5th and 7th chords (with or without the 5th) are passing by just as much as cells with 2-chords, sus4 chords and combinations as D-E-G-A.

The 7th often appears in inverted forms as C-D-F or D-F-G.

- "Why Johnny can't read": formation of the 13th chord in the shape of an arpeggio.

- "Uncle Meat (1992)", bars 161-7: here Zappa is letting the Lydian scale sound in full, as a vertical chord and as an arpeggio chord, transposing it a couple of times.

Blending of notes and harmonic fields (diatonic):

- "Legends of the golden arches", "Regyptian strut, 2nd example", "What will Rumi do?", "The dog breath variations" (1992): combination of a lead melody in parallels

over a vamp, where you're getting all combinations within a scale, almost at will. This effect can also be strongly

present in the examples where Zappa is using two meters simultaneously (see the Roxy section).

- "No, no, no" opening bars, "Uncle Meat" bar 1, "Sofa (1975)", "Watermelon in Easter hay" bar 3, "The mammy nuns", "9/8 Objects": in several examples you'll see Zappa mixing as good as all notes of a scale in a very short time span,

using a scale as something you might call a harmonic field. Combined with the many strings of 9th and 11th chords as well as

the examples with constantly changing scales, bars as these are the clearest expressions of Zappa's

attitude towards harmony: I can do whatever I want, not hindered by any system.

Atonal chords and strings:

- "Igor's boogie I and II": chords in atonal works Zappa wrote for his rock band.

- "Manx needs women": specific use of dissonants.

- "Mo 'n Herb's vacation" opening bars, "Sinister footwear I" bars 20-27: chords in atonal works Zappa wrote for orchestras.

- "Drowning witch" fifth example bars 9-11, "I come from nowhere" bar 5: examples of atonal strings of notes, played ultrafast.

Below at "The torture never stops" you'll find some remarks about preferred and to be avoided chords as suggested in other sources.

Many Zappa compositions have a single melodic line as starting point (like the

"Florentine Pogen" melody from the One size fits all section). The chords can be derived from

such melodic lines by grouping together the notes that are played after each other. Chords in

the sense of notes played simultaneously (I call them chord progressions in this site to make a difference) don't have the same prominent role

in Zappa's music as in classical music. For that matter Zappa doesn't sound "classic". A bar of Chopin can be full of notes,

that, grouped together for their harmony, are often only one or two chords. Zappa's positioning of chords is more direct and the peculiar

thing about his choice of harmonies is that it can vary with each performance. I started this study in 2000 and at that time underestimated

the role of chords. This is to a point due to the releases by the ZFT, showing versions differences, but more specifically to examples of sheet

music that pop up on the net every once in a while. Whereas the album version of "Big swifty" could serve as a good example of a piece being built

around a single melody, its piano part score demonstrates exactly the opposite (included in the Waka/Jawaka section).

"Zoot Allures" is an example of an album where chord progression stand in the

foreground, rather than melodies. The album also includes some keyboard chord progressions, which in

this case are played by Zappa himself.

1. Wind up working in a gas station

Regarding chords "Wind up working in a gas station" sounds as a good rock 'n roll song with Zappa playing all guitars, synthesizer and bass.

An earlier instrumental live version from november 1975 can be found on the ZFT release "Zappa '75 Zagreb/Ljubljana", where this title has the

addition "prototype" to it.

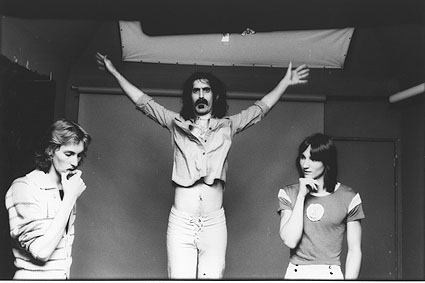

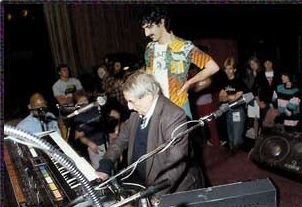

To the right a shot from the album cover photo session with Eddie Jobson (not actually playing on Zoot allures) and Terry Bozzio, who's

taking care of the drum parts.

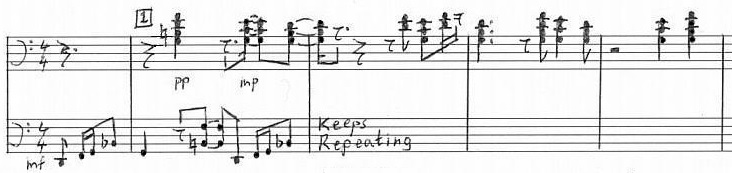

There's one lead guitar and two more overdubbed guitar parts. The synthesizer part is sometimes lightly present in the background (staff 4 of

bars 3 and 4 of the example below). Regarding its lyrics and rhythm however, this song is puzzling. It's a form of poetry with both the lyrics

interfering with the music and the music interfering with the lyrics. Its outlines are:

Regarding chords "Wind up working in a gas station" sounds as a good rock 'n roll song with Zappa playing all guitars, synthesizer and bass.

An earlier instrumental live version from november 1975 can be found on the ZFT release "Zappa '75 Zagreb/Ljubljana", where this title has the

addition "prototype" to it.

To the right a shot from the album cover photo session with Eddie Jobson (not actually playing on Zoot allures) and Terry Bozzio, who's

taking care of the drum parts.

There's one lead guitar and two more overdubbed guitar parts. The synthesizer part is sometimes lightly present in the background (staff 4 of

bars 3 and 4 of the example below). Regarding its lyrics and rhythm however, this song is puzzling. It's a form of poetry with both the lyrics

interfering with the music and the music interfering with the lyrics. Its outlines are:

- 0:00 Little intro with a guitar chord and drumroll.

- 0:05 Theme 1.

The song begins in regular 4/4. Zappa has been looking for sentences with a comparable rhythm, as well as rhyme (though not perfect rhyme). The series "some, from,

thumb, dumb" is rhyming, as does the series "decision, position, education". To achieve this effect better, the first sentence got twisted for its grammar.

"This is a song that might offend some of you" etc. has become the following, where I'm notating the words with the accents in capitals and the 4/4 meter as breaks:

THIS is song might of-FEND you some

[Instrumental bar]

THAT'S the way it is where I come from

[Instrumental bar] If you've

BEEN there too, let me SEE your thumb

[Instrumental bar] Let me

See ...

- 0:21 Theme 2.

"Let me see your thumb", getting repeated over a higher and lower D pedal note by the bass. It's accompanied by a howling feedback C note on the guitar.

- 0:40 Guitar solo.

The example below starts at 0:49, halfway the solo. It's ambiguous about what key it's in, a common factor in Zappa's music. With both

F natural and F sharp turning up, it's a mingling of D Dorian and D Mixolydian. During the solo Zappa is sometimes picking notes, but mostly he's

letting a string glide between G and A. So G# and quartertones are present just as well. Deliberately letting notes get out of tune is in jazz

circles sometime referred to as creating blue notes. In the background you've got two more guitar parts and some

synthesizer notes, played in an irregular improvised form. It's difficult to notate this very precisely. Bars 1-4 are by approximation.

Wind up working in a gas station, section (midi file).

Wind up working in a gas station, section (transcription).

- 0:59 Theme 3.

"Show me your thumb that you're really dumb", repeated four times. What's probably meant as "thumbs up" gets shortened to just "thumb" in order to let

it rhyme with "dumb". At this point Zappa isn't trying to mold the lyrics towards 4/4. Instead of that the rhythm of the spoken words is dictating

the meter. It's a string of 16th and 8th notes, in total 10/16 and subdivided as 3+3+4. The harmony is a harmonic cadance: V-IV-I in C.

During bars 9-10 the song evades to step II of C with Dm7. The next chord is B, not overlapping with Dm7 for any note. With many notes being altered, this transition

comes out as a pretty drastic modulation. The preceding one from D Mixolydian (at the end of the solo) to C only meant a pedal note switch and one note being altered.

- 1:08 Theme 4.

Again the spoken text is directing the meter and its subdivision. All three sentences are thus formulated that they follow a 17/16 meter:

Bar 11: Hey now, better make a decision

Bar 12: [Instrumental bar] Be a

Bar 13: moron and keep your position

Bar 14: [Instrumental bar] You ought to

Bar 15: know now all your education

Next: [Instrumental bar] Or let me

The example above ends with bar 15 at 1:16. The three instrumental bars are a variation upon the bars with lyrics with its length being shortened to 15/16. The bass

pattern is the most constant

element in these bars. Two guitars are playing around the B and Cm chords.

- 1:24 Theme 5.

Till the end the following sentences get repeated by the vocalists, using the same melody for each line:

"Or let me know how you're gonna

Wind up working in a gas station

Pumping the gas every night"

Zoot Allures album:

"Many the camper wants to buy some bite (fish)"

1976 tour:

"Many the camper wants to buy some white"

Like the first sentence the last one gets twisted to let it fit better in the rhythm of the melody. It's about camper drivers looking for something to buy

at the gas station and the words "bite" and "white" (white gas) are chosen because they rhyme to "night".

- 2:29 End.

2. Black napkins (1976)

Next to "The torture never stops", "Black napkins (1975-6)" kept being included

in most concert setlists. I'm dealing with two versions in the preceding FZ:OZ section.

"Pink napkins" is regarding its meter a variant upon "Black napkins".

I'm commenting upon this version in the Shut up 'n play yer guitar section. The pattern in the accompaniment

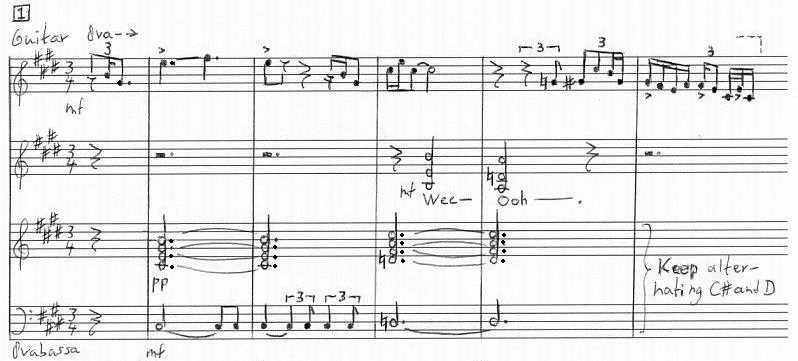

gets indicated, as well as the indecision to play an A or A# over the C# pedal for the various occasions the C#/D schedule is used.

It causes a mingling of Aeolian and Dorian with the keys being C# Aeolian/Dorian and D Lydian.

A presentation of how Zappa informed his 1975 ensemble of how to play the chord alternation can be found at the

Orchestral favorites section of this study at "Black napkins instructions".

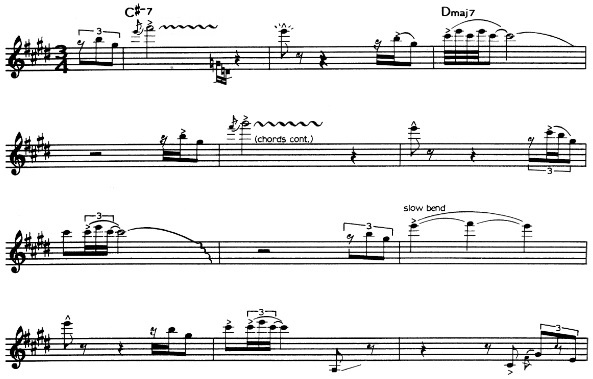

Opening theme from Black napkins as transcribed by Steve Vai (FZ guitar book, page 292).

The A in the first bar is a writing error for an F# (as corrected above). See the FZ:OZ section for more, like

the positioning of the C#m7 and Dmaj7 chords.

Black napkins, 3:27-3:53 (midi file).

Black napkins, 3:27-3:53 (transcription).

This second example is played towards the end. It contains the last four bars of the C#/D alternation, after which a sudden modulation is taking place.

It begins with a series of eighth notes. Bars 9 through the start of bar 12 are in G Dorian. The end of bar 12 through bar 14 are in D Dorian.

After bar 14 the more complicated rhythms return. The D bass pedal gets maintained till the end, with the soloing following D Mixolydian.

I took the FZ Guitar book is a starting point, but notated things a little different.

Sometimes I'm hearing something slightly different. In other instances Steve Vai is using a notation

that requires a higher degree of being able to distinguish rhythms than I can actually hear. Sometimes more simple notations can sound equal to me too.

3. The torture never stops

The next examples are Zappa playing the opening and coda of "The torture never stops" on keyboards, bass and guitar

(most of the original album guitar part of the coda has been mixed out on the CD re-release).

The opening is built around a bass motif and a I-VII chord progression in G Dorian. The VII chord can either be seen as an 11th

chord or VII 5th mixed with I 5th continuing.

The coda is basically regular, but because of the mixed chords on the pedal note and the frequent use of fourths some unconventional flavour is added to it.

The torture never stops, opening (midi file).

The torture never stops, coda (midi file).

The torture never stops, opening (transcription).

The torture never stops, coda (transcription).

The second example is the ending cadence of this song, also in G Dorian, that goes as follows:

bar 1 through 4: various chords upon G as pedal note.

bar 5: IV 7th, I 5th plus C.

bar 6: VII 5th, V 5th.

bar 7: I 5th. For a moment it sounds like the melody is ending as a deceptive cadence with IV 5th (G and C), but the bass takes this

C as a passing through note for D. So it ends regularly with I 5th, though with the C still sounding in the descant staff.

Bars 1-4 are some of many examples showing that Zappa liked to use

any kind of harmonies within a scale. It's a non-standard progression with:

- Gm.

- Gsus2.

- Fsus2.

- Fadd2.

- Fsus2.

- Gm7 (no 3rd).

- Fsus2.

- Gsus4.

In traditional harmony extended chords, including sus2 and sus4-chords, are seen as dissonant, in need for a resolution to a triad. It's quite clear

from many examples in my study that Zappa handled these chords as independent chords, like in the one above. Zappa didn't set traditional harmony aside

but extended it to being allowed to do anything without an obligation to follow the "rules" you had to learn in harmony classes.

Zappa kept playing "The torture never stops" live, as well returning and extending the original tracks for his "Thing-Fish" CD from 1984.

Other versions in this study:

"The torture never stops (1977)": the opening bars of the solo from the six Halloween concerts from 1977.

"The torture never stops (1980)": the monumental live version from 1980

with a section going entirely different and several solos.

"The 'torchum' never stops": for "Thing-Fish" Zappa added a block, that he

also played live separately as "The evil prince".

"The torture never stops (1988)": another live version with the opening bars

beginning somewhat differently from the example above.

4. Ms. Pinky

"Ms. Pinky" and "Find her finer" are the easier pop songs on "Zoot allures". "Ms. Pinky" has only one theme for both the verse and the chorus.

Halfway there's a little instrumental section, still using the theme.

Like "The torture never stops", the tracks from "Ms. Pinky" got re-used for "Thing-Fish". The song got renamed as

"Artificial Rhonda" on the latter CD. Three examples are included in the Thing-Fish section

of this study. The subject of Miss Pinky is also coming by in "Lonely person devices", of which song I've included outtake in the FZ:OZ section of this study.

Ms. Pinky, 2:28-2:49 (midi file).

Ms. Pinky, 2:28-2:49 (transcription).

Towards the end there's another little instrumental section with a guitar solo. The example above contains the last four bars.

This guitar solo is in A Dorian. Next the final version of the verse is coming by. Like the "Artificial Rhonda" examples it mingles A Mixolydian and A Dorian.

The dense way bass, synthesizers and guitars are playing together make

it difficult to come at an accurate transcription, or a midi file sounding alike. The lead guitar from bars 1-4 is playing in manner with much legato, which my midi editor can't

represent properly. When you're comparing the theme as it's played here with the three examples from "Artificial Rhonda", you can notice smaller variations upon

it occurring all through this song.

5. Find her finer

"Find her finer" knows the standard verse-chorus structure and is built around a bass lick. The example below is its instrumental intro of four bars,

played between 0:00 and 0:09.

Find her finer, intro (midi file).

Find her finer, intro (transcription).

Its basic idea is a I-IV-I progression in D Mixolydian, but because it is getting played around in layers, the actual harmonies are much richer and mingled.

The staves represent:

- Staff 1: Zappa speach-wise singing "ha, ha, ha" in bar 4, as an introduction to the regular lyrics.

- Staves 2-3: Don van Vliet on harmonica, recorded in two layers.

- Staff 4: Zappa on keyboard.

- Staff 5: Zappa on accoustic guitar (pitch notation as it sounds).

- Staff 6: Terry Bozzio on drums.

- Staves 7-8: Zappa on bass and possibly synth. bass, with the sound and volume being different in the right and left channel.

During bar 1 the harmonica chord is G7. With Zappa adding C-E on keyboard to it, the total sounding chord becomes G9.

6. Friendly little finger

In 1976 the band did a one-time visit to Japan, which explains the Japanese characters on the "Zoot allures" album

sleeve. "Black napkins" was recorded live at Osaka, the "Zoot allures" opening from "YCDTOSA III" is taken from the Tokyo

concert. Some eastern influences can be found in "Friendly little finger", not only because of the sound of the opening theme, but also

by the various melismatic movements in this theme and the bass lines, that accompany the solo. "Friendly little finger" is an

extraordinary solo in many aspects. It is best known as an early example on record, where Zappa applied a technique

that he called "xenochrony" (strange synchrony). In the liner notes for "Rubber shirt" from "Sheik Yerbouti" he explains the idea behind it.

Xenochrony is laying a recording over another track, that was recorded completely independent of it, followed by

a resynchronization. It is thus different from an overdub and different from putting tracks behind each other or lying tracks over each other

without adapting them. The resynchronization has the effect of suggesting that the tracks are reacting upon each other.

The transcribed solo section indicates this. A hand-made transcription by me is not proof of course, but the two equal beats pointed at with

an arrow in bar 3 are clearly audible on the CD at 0:39-0:40. If it wasn't resynchronized, that would be too much of a coincidence.

In this case the solo (a dressing room recording without accompaniment) and the drum part are from different occasions. The

bass was overdubbed later on after the resynchronization was completed. See the One shot deal section for more about

xenochrony.

Friendly little finger, opening riff (midi file).

Friendly little finger, 0:36 till 0:51 (midi file).

Friendly little finger, opening riff (transcription).

Friendly little finger, 0:36 till 0:51 (transcription).

The melody of the opening theme is using unusual harmonies, forming two 11th chords, namely D-E-B-A and G#-A-E-D. The lick

is played by various snare and percussion instruments, mostly parallel, sometimes taking some side steps as in bar 4.

In bar 6 the bass starts playing its own lines, as it will continue to do during the solo that follows upon the opening theme. At various instances this solo

isn't using traditional western scales. In bars 3-5 it applies for instance the sequence C-Eb-F#-G-A-B over D pedal.

It sounds unorthodox this way. The solo remains being played over a D-pedal, but the scales change frequently. In bar 6 the key

turns over to D minor (Aeolian), in bar 10 it becomes D Lydian. At the points where the guitar solo is playing sustained notes, as

in bars 1-2 and 9, the bass is taking over the soloing. Because it's overdubbed it could do exactly that. Zappa is playing

the bass here himself as well and it clearly isn't of the normal accompanying type as during live concerts.

7. Wonderful wino

This song stems from 1969, at first a Jeff Simmons song for a solo album. He played the music to Zappa, saying that he didn't know what lyrics it should have.

So Zappa proposed he could write them. Since he wasn't a drinker or a drugs user, he only occasionally wrote songs about this subject, even though

its presence in the rock-business was ubiquitous. He liked to write about everything happening in society, but this is something he apparently

couldn't relate to easily. "Wonderful wino" is about an alcoholic with Zappa singing it in the first person, thus acting as if he himself was a wino. Other

explicit songs about drugs are "Any downers" and "Cocaine decisions".

Wonderful wino solo, 2:59-3:18 (midi file).

Wonderful wino solo, 2:59-3:18 (transcription).

Other than on the Jeff Simmons album and the 1970/1 setlist for his own band (as included in "Playground psychotics"), the "Zoot allures" version of "Wonderful wino" also contains

some musical contribution by Zappa in the sense that the song ends with him playing a solo. This soloing starts at 2:34 and takes up a minute. It has Zappa

playing bass, keyboard and two to four guitar lines. The accompanying figure is a continuation of the figure used for the last sung part of the song. As it comes to his

soloing he has sometimes called himself a one-chord guy and in this case this can be taken literally. It's an A as bass pedal and a rhythm guitar playing the A triad.

Every four bars the keyboards play two-note chords, E plus A, followed by E plus G. The last chord extends the harmonies to larger chords.

Depending at the spot you're listening at there can also be a B, D and/or a C natural to it. At 1:54 you can brightly hear the A triad with E-G on top of it, forming A7,

at other points it's more difficult to discern the exact notes involved. At bar 9 Zappa switches from A Mixolydian to A Dorian. He liked the accompaniments

of his guitar solos to remain simple, to be able to do whatever he liked on top of it without interference from it. As he's doing in this little but fine solo and the also

small one from "The torture never stops".

8. Zoot allures (1976/84)

The "Zoot allures" guitar solo is made up of four blocks:

a) 0:00-0:38. Opening with a sequence of chords from different scales. Next to the "Zoot allures" execution, you've got

other versions on "Does humor belong in music?", "YCDTOSA vol. III" and "Make a jazz noise here". There are two more

performances on ZFT releases. All versions follow the same general structure. At a detail level there are many differences, as you can

for instance see by comparing the openings from "Zoot allures" (1976) and "Does humor belong in music?" (1984). The main differences, however,

lie in the guitar solo (block d), that is getting far more space in the different live versions.

See "Zoot allures (1984)" from the Does humor belong to music? section

for such a solo.

Zoot allures guitar solo, 1976, 0:00 till 0:14 (midi file).

Zoot allures guitar solo, 1984, 0:00 till 0:14 (midi file).

Zoot allures guitar solo, opening bars/section (transcription).

Zappa playing Zoot allures at The Pier, N.Y.C., 1984 (Does humor belong in music DVD)

Both examples last as long and cover the same, but the 1984 version is actually played faster. This is caused by the chord from bar two being maintained

one bar longer in 1984. Bars 6 and 7 respectively contain regular chords, G and Dm7.

The chord from bar two has been recognized by Brett Clement as the so-called So What chord, though not as extensively used as he suggests.

This chord can be heard on "So what" from the Miles Davis album "Some kind of blue", and has been given a special status in jazz circles.

Upon D# it's built as D#-G#-C#-F#-A#, thus three fourths followed by a major third. It's very much a guitar chord, because, upon E, these intervals are

the standard

tuning of strings 1-5. And by hitting all open strings, you would only be doubling the E, still leaving the So What chord sounding. In bar two from the

1976 version the A# fails, while in

bar two from the 1984 version the D# is absent (apart from the melodic D# in the bass line).

There are also instances where the chord can be heard

to the full. An example is added from the Clement study with 2:32-2:48 from "Does humor belong in music?". As briefly indicated

in his example, this gets followed by a pedal note guitar solo in A Mixolydian, instead of the alternation in C# Dorian on "Zoot allures".

b) 0:38-2:51. Central theme, a chord progression, following a modulation scheme.

The next example is the main chord progression from the "Zoot allures" guitar solo (pitch notation as it sounds). The fast key changes are

responsible for the solo's harmonic tension.

Zoot allures guitar solo, 0:38 till 1:44 (midi file).

Zoot allures guitar solo, 0:38 till 1:44 (transcription).

- Bars 1-5. It starts in E with the

chords I 5th, I 5th, V 5th plus E continuing, I 5th.

These specific chords can first be heard on the "Zappa/Erie" box with the 1974 concert at Erie, namely during the solo of

"Dupree's paradise".

So the idea of setting up a guitar solo like "Zoot allures" must have existed in Zappa's mind for longer. You can find it at the end of my "Dupree's paradise"

description from the YCDTOSA vol. II section.

- Bars 6-8: Hereafter it shifts into the V 5th chord of F sharp, with G sharp as the common note

with the previous chord. This key change is confirmed by a bass riff.

- Bars 9-16: Repetition.

- Bars 17-21: The solo returns to V 5th of E, followed by several passing through

notes from E Minor (or Dorian).

- Bars 22-32: The three chords with their preceding triplets are combining I and V 5th of F sharp, G and A (because of the E pedal for this chord

in the example above, this last instance can also be identified as E Mixolydian). This sequence is created by transposing

these figures up, first with a minor second, next with a major second.

c) 2:51-3:06. Return of some of the chords from block a), followed by a transition towards a guitar solo.

d) 3:06-4:12. Improvised guitar solo over a I-IV alternation in C# Dorian, slowly fading out.

A photo of Janet Walley wearing a T-shirt with Zappa's Zoot allures album cover on it. Source: the Halloween 77 booklet as included as a pdf file

in the 6-concerts-on-a-stick version.

As a fan she could participate in Zappa's Baby snakes movie, the audience participation part. In the booklet she gets a chance to tell how it happened.

She became the wife of Denny Walley, guitar player in Zappa's band

for a number of tours.

9. Disco boy

On "Disco boy" there's some greasy rock 'n roll playing with thick guitar and synthesizer sounds, like the "doo-dee" block in the middle of the song:

Disco boy, section (midi file).

Disco boy, section (transcription).

This progression, divided over four bars is I-IV-I-IV, IV, I-IV-I-IV and VII-I in B Mixolydian. An overview of the construction

of this song can be found in the Ludwig study, page 224. This page contains the lead melody from both the verse and the chorus, while

my example above stems from the instrumental bridge. The A sharp in the presets of his transcription must be a writing error: it should be an A natural.

At the bottom Ludwig indicates as specific characteristics: bombastic synthesizer sounds,

rock 'n roll rhythms and distorted guitars. When you listen in detail to how Zappa created this effect, you can hear that it's carefully planned via

overdubbing.

HATEFUL PROGRESSIONS AND THE CHORD BIBLE

a) Hateful progressions.

As it comes to chord progressions, Zappa called the progressions that you had to write down in harmony classes "hateful", especially

the ones with the chords of resolution. He indeed liked non-standards chords as sus2 and sus4-chords, as well as extending chords up to the 11th and 13th.

The confusing thing about Zappa is that, whenever he claims to dislike something musically, you'll find examples of him doing exactly

what he dislikes. The reality about his harmonies is that he followed common paths just as much as he liked to deviate from it. This is already

talked about above and other parts in this study. Dissonant chords can, but don't have to resolve, certainly not in Zappa's music. But it's

also exaggerated to suggest that they have to in all classical music.

b) The chord bible.

In interviews Zappa has mentioned that he worked with a chord bible for his orchestral works from around 1980. These are the newly written,

mostly atonal works for the L.S.O. and Boulez albums. The content of this chord bible hasn't been published, nor is it known for which specific

titles he used this set and to what extent it got applied. Attempts to estimate what might be in it have been done by Brett Clement. See his

2009 study in the literature list. Some side remarks have been made by me (you can find a link to a pdf file in the left menu with Brett's response to me),

but in general I have no judgment upon this. Anything you say can't be verified, simply because this chord bible is stacked away in the ZFT archives.

Some more about this topic is briefly passing by in the L.S.O. section of this study at "Mo 'n Herbs vacation".

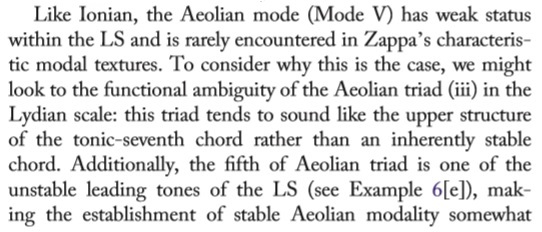

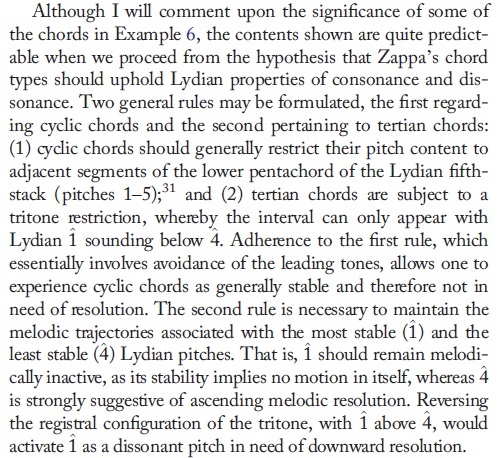

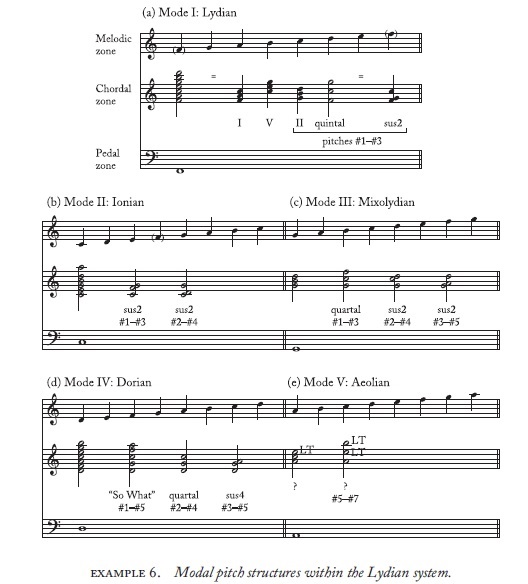

PREFERRED AND TO BE AVOIDED CHORDS IN A LYDIAN SYSTEM

Brett Clement has also constructed a table with preferred and prohibited chords for Zappa's instrumental diatonic music. This is the more interesting

part of his Lydian theory for here this theory is getting consequences. My study is quite different in this matter in the sense that I don't have such

theories and tables. Brett is the first to come up with a theory about Zappa's diatonic instrumental music, and because of that it has been heralded

by a number of people as a break-through. It tries to give a musicological explanation why:

- Zappa has a preference for Lydian and Dorian over the other modes.

- Why some chords are characteristic, while others are unstable.

- Why Zappa's music lacks a sense of tragedy.

- Why Zappa is inclined to avoid the tonic in melodies, when playing in Lydian.

These four subjects are interrelated, being a consequence of what he himself describes as Zappa following a Lydian system.

Because I'm simply saying that Zappa just did anything in any scale, there doesn't

have to be much discussion about the preferred chords. Zappa indeed uses them. It's the prohibitions that are teasing.

Brett calls a number of chords unstable or dissonant within his Lydian system. Chords should avoid the inclusion of leading tones from this Lydian system.

This means that in Aeolian/minor the triad and the sus2 and sus4 chords upon the tonic are to be avoided. In Dorian this goes for the sus2 chord.

Brett doesn't go as far as excluding the triad in Ionian in his table, but his comments upon the fifth of the minor triad

might imply that this chord should be seen as unstable too (for its third).

In his article this gets stipulated as some sort of musicological formula, but in his response to me it's more down to earth. He's asking readers to play it

and experience the dissonance.

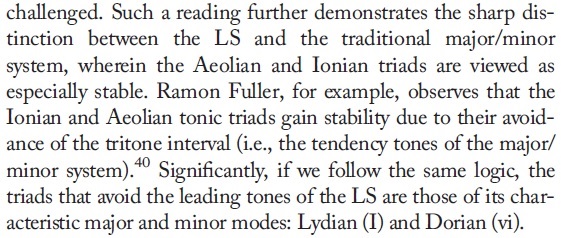

As Brett also notices himself on page 154-5 of his article, his rules do the opposite of traditional harmony:

Playing triads upon the major and minor tonics

is about the most normal thing you can do in Western music. All details

of Brett's reasoning can be found in his own study and his response to me (left menu), as well as my objections and examples to the contrary,

so this doesn't have to get repeated here. One has to consider the following:

1) Brett is asking you to switch your coordinates of what's consonant and dissonant when listening to Zappa's diatonic instrumental music.

In this case one has to experience the rules as presented further below, rules that don't exist in traditional harmony.

2) Don't make this switch when listening to his songs (with lyrics).

3) A couple of compositions exist in both instrumental versions as with lyrics (e.g. "Let's make the water turn black", "Take your clothes off while you dance",

"Dog breath", "Montana" interlude and "Bogus pomp").

4) Several compositions contain their themes being played both instrumentally and with lyrics (e.g. "Miss Pinky", "I have been in you" and "Wild love").

Just for conceptual reasons his way of reasoning already raises question marks. Is it humanly possible to redefine one's definition

of consonance depending on the context? And only when listening to Zappa (Brett does not claim any other composer follows his Lydian theory).

Personally I would say this is not feasible, but you can test it yourself by listening to the examples below. Secondly the status of a range of compositions becomes problematic,

the ones that include themes that get played both instrumentally and with lyrics. This situation is thus peculiar,

that one might ask if an academic journal should take the risk of publishing it. The editor

of Music Theory Spectrum at that time, who approved this writing, is Mark Spicer, professor at the Hunter College, University of N.Y. When I informed him of my

objections, this article had passed the submission procedure by long, being peer reviewed and all, and stood in front of the queue for being published.

Mark Spicer wrote me the following:

"You offer a transcribed example from "The Torture Never Stops" that purportedly shows a sus2 chord

on a Dorian tonic. First, the presence of one example (or even many) does not contradict Clement's theory.

Second, the sus2 chord in this particular example is easily explained as a G-minor triad with the A being

a passing tone from B-flat to G, rather than a self-standing sus2 chord. In other words, the A could be

considered not to be part of a sus2 chord but purely a melodic phenomenon."

So noted. Brett has stated his rule of Lydian consonance three times in a row and Mark Spicer wishes to maintain its correctness.

Moreover you can notice that Mark Spicer is mixing up a statistical finding and a musicological explanation. When Brett's Lydian rules are giving an explanation

why Zappa should avoid certain chords, then it's not about how many examples to the contrary exist, but about how they sound: one should be able

to actually hear the unstability of these chords in a Lydian system.

In his 2009 study Brett objects to the presence of the dominant 7th chord in his Lydian system. Its resolving tendencies would challenge

the supremacy of the overriding Lydian tonic. In his article

he newly formulated a rule against the dominant 7th chord family upon the Mixolydian tonic, the only scale that has these chords upon its tonic, the chords

Brett is concentrating upon. These arguments are different, but don't exclude each other. In my reaction I'm addressing myself to both versions,

but in his response Brett claims that he only objects to the dominant 7th chord in Mixolydian. Then it does get inconsistent, because that

would mean that playing V 7th - I in major would now be ok in his Lydian system, something he objected to in 2009 (see the Burnt weeny sandwich section from this study

at "Overture to Holiday in Berlin" for the details).

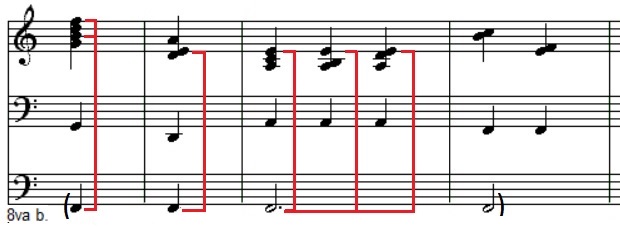

Brett Clement. A new Lydian theory for Frank Zappa's modal music, page 152. The two rules that define consonance/dissonance in

a Lydian system.

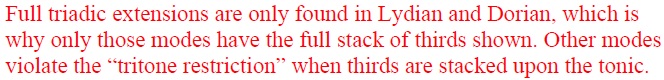

Table A. Brett Clement. A new Lydian theory for Frank Zappa's modal music, page 151. The preferred chords of a Lydian system.

Brett Clement. Response to Kasper Sloots, page 97. This further explains the stacking of thirds in the table above. The tritone restriction

means that, in case of F being the overall tonic of the Lydian system, this F can't be played on top of B. The then created tritone

dissonance would leave the F in need

of a resolution, undermining its stable function in the Lydian system. In the Ionian table the F is left out, in the Mixolydian table the stacking

of thirds comes to a halt when reaching the F. In the Aeolian table the first rule more generally already creates a problem at the triad (the ? with LT standing for lead tone),

as explained above in the citation from pages 154-5.

What Brett is calling "lead tones" from his Lydian system are pitches 6-7 from stacking fifths. In case of the example above this series is F-C-G-D-A-E-B, causing the E and B being

"lead tones". He sometimes calls them unstable, other times dissonant. In case of his own example (see below) violating the first rule he's talking about a "very striking and dissonant effect".

In its standard meaning a major 7th of a scale is generally seen as a lead tone. Above the E is also

the lead tone of F Lydian in its standard meaning. In Brett's system it's a "lead tone" for all scales.

THE DOMINANT 7TH

Brett Clement. Response to Kasper Sloots, page 106 (blue is me, red is Brett).

Yo' mama, Sheik yerbouti, fragment (midi file).

Yo' mama, Chicago '78, fragment #1 (midi file).

Yo' mama, Chicago '78, fragment #2 (midi file).

Yo' mama with Mm7 (note examples).

The first example is the one Brett is referring to, the other two are from the "Yo' Mama" solo from "Chicago '78".

They have in common that the overall harmony is often E11. When it sounds ok with E11, it automatically sounds ok

with E7 too, at least to my ears. In his response Brett is saying things like the first example isn't really E11 but a D-chord on top of an E-chord.

But it's always possible to split larger chords: E11 is identical to a D triad on top of an E triad. For the overall sound

this is irrelevant, certainly when you're talking about consonances and dissonances. The total you're hearing is E11, no matter how you call it.

In the above examples an explicit E7 chord is added as an extra sustained chord, the experiment Brett is asking you to do. It doesn't sound awkward to me at all.

Exercise #4 (1973), opening bar (midi file).

Whisky souflée, section (midi file).

Call any vegetable (1971), opening of the solo (midi file).

The Gumbo variations, opening (midi file).

Promiscuous opening (midi file).

Red tubular lighter (midi file).

Mr. Clean (midi file).

Moldred (midi file).

Examples of Zappa using Mm7 (note examples).

See also above at "Find her finer" for the use of D9 during bar 1, with the harmonica staves explicitly using D7. Some examples by others:

- Zappa's own handwritten "Arabesque" score is an early example of him being pretty versatile as it comes to keys and chords.

In notations like this the root of a chord is also to be taken as the bass note. The Mm7 returns a couple of times (extended with a major 9th).

Chromatic notes are also occurring. See the Projects section from

this study, where you can also hear how it sounds. In bar 6 from my 2nd example both the melody and chord are following G Mixolydian.

- "Fifty-fifty", pages 43-51 from the Overnite sensation guitar book, transcribed by Paul Pappas. Three examples are also present in my Overnite sensation section.

It follows a modulation schedule, using the Mixolydian mode as the central mode. I agree with Brett that it's far away from purely Mixolydian,

but the pattern can be discerned and there are sufficient bars using the Mixolydian mode as basis.

- "Stink-foot", page 83 from the Apostrophe guitar book, with Andy Aledort indicating C7 for the opening of the guitar solo.

This is not pentatonic blues, as Brett suggests in his response, only blues-like if you wish, using the full Mixolydian scale.

This topic is getting dealt with at large in my Burnt weeny sandwich section and my Imaginary diseases section at "Been to Kansas city in A minor".

The only thing I can agree with is that at several other points during this solo, Zappa is also using the Eb from C Dorian.

In the second example from the 1988 solo you can hear Zappa extending the overall harmony to C11.

- "Can't afford no shoes", pages 46-7 from the One size fits all guitar book, transcribed by Addi Booth. Idem.

- During the first solo from "D.C. Boogie", Tony Duran repeatedly plays a F#-5 chord over a D pedal. Apparently he didn't consider

D7 a harmony one should avoid when playing with Zappa.

- During the first bar from my "Father O'blivion" (Sydney 1973) example George Duke plays G7 while Zappa is briefly soloing in G Mixolydian.

In traditional harmony, the dominant 7th chord is seen as dissonant, as well as a tritone. G7 resolving to C is the archetype

example of a resolving progression. But it's also a normal chord in traditional harmony, certainly not one that should be avoided.

It's not even a rule that it must resolve.

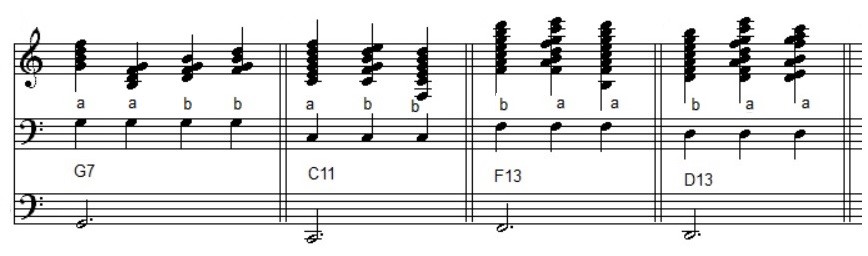

Brett does use the word prohibited on page 131 of his 2009 study. Moreover he's using his tritone restriction for impeding

the stacking of thirds to the full in Ionian, Mixolydian and Aeolian. Wouldn't that be odd for someone who claimed that he loved extending

chords to the 11th? In a very abstract way I can understand how Brett is reasoning, but in a practical sense it's a no. The above

examples sound perfectly normal to me. And if you find they don't, shouldn't then Zappa have instructed his band by saying something like

"please don't play note #7 on top of #3 when we're in the Mixolydian mode, that destabilizes the overall Lydian tonic of my instrumental music".

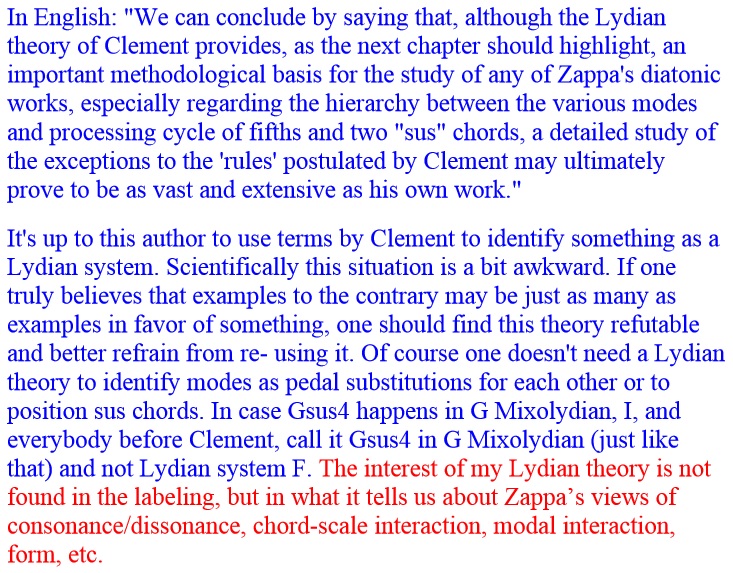

Brett Clement. Response to Kasper Sloots, page 109. I'm citing this to stress the importance it has to Brett to abide to the rules of a Lydian system.

As said, in this response I'm reacting to both his 2009 and 2014 writings. If you concentrate on his 2014 writing only, a number

of examples of Mm7 would indeed fall off. On the other hand the Mm7 chord in Mixolydian is not the only chord that can violate his tritone

restriction. And, as you can read in the Roxy and elsewhere section at "Son of Orange County", he would like to extend its significance to melodies too.

Systematic adherence to the tritone restriction would, in my opinion, lead to another table and conclusions than above. All chords know inversions and

different ways of voicings. In 2009 Brett talked about a general problem with the Mm7 chord in his Lydian system, in 2014 he newly introduced his tritone restriction. Strictly speaking that

would mean that two of the three inversions of the G7 chord in Mixolydian would not violate the tritone restriction (above position a is violating the tritone restriction, b isn't). On the other hand F13 in Lydian and D13

in Dorian can be voiced/inverted so that they do violate the tritone restriction. A few voicings are shown above, where I've avoided the minor second (all chords

therefore aren't sharply dissonant).

One has to realize that when people are talking about chords in its standard meaning, it

includes all inversions and voicings. Zappa often notates his harmonies by the chord type only, which, in a number of situations, would mean that you can either play it

with or without a tritone violation. This, of course, isn't an issue when this doesn't bother someone.

TRIADS AND SUS-CHORDS IN AEOLIAN AND DORIAN

Brett Clement. Response to Kasper Sloots, page 113 (blue is me, red is Brett).

His choice of words around "instrument of your choice" is peculiar. Logically that would mean one could test his first rule for Aeolian too

in this manner and that it applies to music in general. Let's assume this is a slip of the tongue and that he means in the context of Zappa's

instrumental music.

Outrage at Valdez, bars 1-3 (midi file).

Pygmy twylyte (A token of his extreme), solo section (midi file).

The idiot bastard son, intro from the YCDTOSA II version (midi file).

Sheik Yerbouti tango, bars 9-12 (midi file).

Peaches III, main theme (midi file).

Dupree's paradise (1974, Erie), bars from the guitar solo (midi file).

The curse of the Zomboids, bars from the guitar solo (midi file).

Examples of Zappa using the triad and suspended chords upon the Aeolian and Dorian tonic (note examples).

Regarding the first example, Brett doesn't really deny it's an example to the contrary, just calling it flawed (Response to Kasper Sloots, page 123).

So, according to Brett that would be a "second" example violating his first rule, see below for the first one, but who is hearing "the very strong and dissonant" effect here?

Regarding the second one he doesn't deny this either. Instead he writes: "I won't bother to respond here. Since this is improvisation by George

Duke, and therefore not composed by Zappa, it doesn't apply to the

conversation". It is improvised accompanying Zappa, landing on an official album, but how can that affect how it sounds? How can it sound unstable if Zappa would

have put it on paper, and normal when George is playing the same on keyboard, like Brett is suggesting himself ... "instrument of your choice".

The least Zappa could then have done is instruct his band by saying something like "don't play a triad, sus2- or sus4-chord upon the tonic when we're in Aeolion,

that creates a dissonance with the overall tonic of my instrumental music". As it comes to the third example Brett does deny it's in D Dorian. Instead he claims

it's in A Dorian with the F in the sus2 progression being a non-scale note. I agree that it's possible to reason like that for theme 1 of this song (where the sus2 sequence

moves over to an A pedal), but

certainly not for the intro. Check it yourself, bars 2-5 follow D Dorian and they don't move over to an A pedal, but a chromatic passage. Ruth Underwood plays the sus2

sequence separately on the Classic albums series as sounding typical of Zappa (see the YCDTOSA vol. II section of this study for the details). Then you want people to hear it as in A Dorian with the F being an altered note?

Regarding the Sheik Yerbouti tango and Peaches III, Brett doesn't deny that these examples can be interpreted as examples to the contrary. In this case

he's arguing that these two examples don't count for not following the pitch structures of a Lydian system. Kind of vague

and arguable (it's instrumental, the area Brett wrote his Lydian theory for, it's not a parody, it's not typical "functional harmony" ...). If you would allow it to be discussed, would then an outcome of a discussion determine if you're hearing it as consonant or not? Personally

I'm calling something consonant or dissonant, independent of the name somebody wants to give to the bars where they occur.

The "Dupree's paradise" example wasn't released when Brett wrote his response. It's an example of Zappa himself playing F#m and F#sus4 upon the F# Aeolian tonic.

The same goes for the 1972 version of Montana, with a vamp in F# Aeolian. You can frequently hear the F#m chord during this solo. In section H of

"The grand wazoo" Zappa prescribes the Bm7 chord in B Aeolian (like the stacking of thirds in Mixolydian halts at the triad in Brett's table, it gets questioned altogether in Aeolian).

The main progression from "Any downers" is an example where the context is getting problematic from the angle of a theory for instrumental music. When it has lyrics

it wouldn't be relevant, but when Zappa starts soloing over it, one is expected to consider this unstable. Of course this doesn't play any role when this theory has no meaning

to you, it sounds just as normal instrumentally as with lyrics. "The curse of the Zomboids (I'm the slime)" example comes from the 2023 "Overnite sensation" Deluxe edition,

a passage in F# Aeolian with the F#m chord. The first bar from the Blessed relief example contains another example of a sus2 chord upon a Dorian tonic. Over an F# pedal, George Duke plays C#-G# and

Zappa a C#. It is an improvised studio recording, but if it was to sound unstable, something Zappa wouldn't do on paper, then why not replace these bars?

The band always did multiple takes with Zappa editing the results. The "Filthy habits" example comes from my 2025 update, the part over a C pedal (both Brett and me

missed it in our 2015 discussion). It includes Cm, Cm7 and Csus2(add7) in Aeolian.

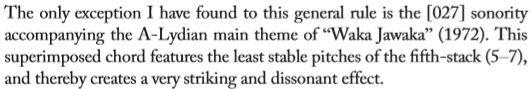

Brett himself claims that he only encountered one example to the contrary, the citation below from page 152 of his 2014 article. Pitches 5-7 from stacking 5ths in A Lydian are C#-G#-D#,

voiced as a C#sus2 on "Waka/Jawaka". This example is present in my study (see the Waka/Jawaka section).

In case of Lydian, and Lydian only, the overall Lydian tonic of Brett's Lydian

systems can actually be heard. In this case you can hear the G#-A dissonance (the G# from the chord and the A by the bass).

Still it's not as striking a dissonant accompanying chord as D#-E-G#-A would be, an incomplete 13th chord, with both minor seconds from the Lydian scale in it.

While Brett is concentrating upon chords upon the tonic, one might reason his rules can also be applied to the corresponding

scale steps from the other modes. Brett himself is here opening this door by presenting a sus2-chord in Lydian upon step 3 of this scale, which is the main reason I'm pointing

at this remark. Similarly his rules can be applied to other

chords too, the triad and sus4-chord upon step 3 in Lydian should be heard as unstable too, as well as the sus2-chord upon step 6. Likewise this can be done for

the other scales. This brings us back to the Mm7 chord. In his 2009 study he seems to object to the Mm7 chord not only upon the Mixolydian tonic, but in general,

presenting the Mm7 upon step 5 in Ionian as not belonging to a Lydian system. In his response to me, however, he states that he objects to Mm7 in Mixolydian only. Aren't we then reasoning

in a circle? Again: Brett himself has opened this door.

As said, on a very abstract level it's possible to follow Brett's reasoning. Basically it needs two requirements from the listener, when listening to Zappa's instrumental

diatonic music:

- You always have to be aware what the overall tonic of the Lydian system is (staff 3 below).

- What Brett is calling "lead tones" should be avoided. So forms of dissonances with this overall tonic should bother you for destabilizing the Lydian system (chords 1-5 below).

- Chord 1: the upper note of the tritone from this G7 chord is the overall Lydian tonic F from staff 3, violating Brett's tritone restriction.

- Chords 2-5: the E in these Dorian and Aeolian chords creates a dissonance/unstability with the overall Lydian tonic F. As long as this Lydian tonic isn't actually played, I'm not hearing

it. When forcing yourself hearing it, by playing staff 3 too, wouldn't that create an inconsistency? Wouldn't the key then not become Lydian by definition?

- Chords 6-7: chords in Lydian, incomplete F11 and Fmaj7 chords. That is what in particular sounds dissonant to me, audible minor seconds.

Brett's Lydian theory is what sometimes has been called an "academic" theory, a theory that you can construct in your mind, but that can't function in reality.

So far I'm the only one who has openly questioned it in print (pdf-file, article or book). By implication Daniel Schröder has done this, see the left menu

at the Lydian theory for some comment.

Charles Ulrich and Chanan Hanspal have given their full-hearted support of this theory,

both after a discussion about it had arisen, so there are people who find Brett's way of reasoning persuasive.

Something one has to realize is that the Lydian theory can't live without Brett's rules of consonance/dissonance. Without them it can't explain anymore what it wants

to explain. It would become an empty shell. If there weren't any rules, Brett's example 6 from above would come to look as:

Table B. The stacking of thirds and positioning of sus-chords (incl. inversions) upon tonics. This isn't a Sloots

theory, a revised LCC theory, a revised Lydian theory or whatever. This is common knowledge. And this is how Zappa is actually using these chords.

In case you would reduce Brett's theory to something as meaningless as that he has shown the importance of pedal notes and sus-chords in Zappa's music,

you can immediately see that there would be no musicological reason why Zappa would prefer Lydian and Dorian over Mixolydian, Ionian and Aeolian, the thing

Brett wanted to explain. Moreover, when you start reducing it, it can't be Zappa's original, highly codified solution anymore, which is what Brett's thesis says.

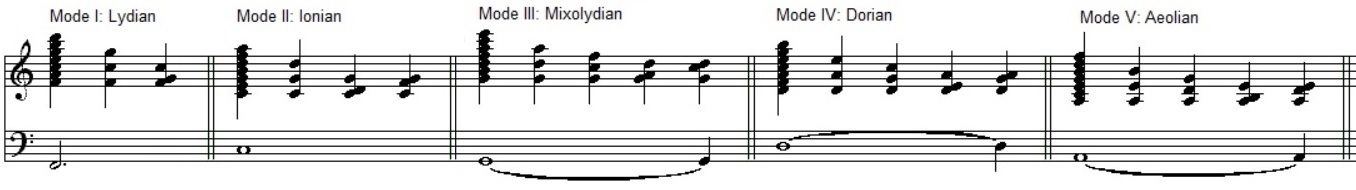

Martin Herraiz wrote his study before Brett's Response was made available. Martin writes:

About which I'm saying (in blue) and Brett (in red):

To me this doesn't make sense. How many examples to the contrary does one need to reject Brett's theory? Moreover, as already said, Brett

is giving a musicological reason why some chords should be avoided. Then it's not about how many examples to the contrary might be encountered, but

how they sound. Even I am not suggesting there might be just as many as there are in favour. What I am saying that these chords sound perfectly normal in the context

of Zappa. The second argument is strange too. Is Martin here suggesting that someone better needs table A instead of table B for relating modes and sus-chords?

Or that people before Brett had problems with relating scales and sus-chords, table B not being common knowledge? I know that sounds silly, but what else could it mean?

The only real difference between table A and table B is that Brett calls a number of chords dissonant or destabilizing in his Lydian system.

Martin, "yetanother", is here trying to throw with some mud (screenshot from the Zappateers site). Between the lines you can notice an argument fails. The actual reason why people as

Martin are so eager to associate themselves with Brett's theory can only be its suggestive nature. It's all written in a highly-educated form, way more

complex as I or Wolgang Ludwig are describing examples. It gives people the idea that something at a higher musicological level is happening, a point

where you can get at conclusions other people couldn't come up with. And you indeed have people who can't accept the idea that a composer ever set out to compose without any system. You indeed have people like

Mike Pierry who start cheering when Brett found out that Zappa used a system after all:

This situation has spoiled a lot. With reputations involved you know a number of people will do anything rather than admit mistakes. It might take years, maybe decades,

before this normalizes. I'm just the first to have overtly questioned Brett's Lydian theory.

It's highly unlikely that this citation of Terry Bozzio (Orchestral favorites 40th anniversary booklet) is directly related to the discussion above. Rather it's a sponteneous

estimation of Zappa's music and this is how people not acquainted with Brett's theory normally talk about his music. When you take it literally it denies the existence of rules,

thus also the ones that define consonance and dissonance in a Lydian system.

INTERVALS IN DIATONIC COMPOSITIONS

Since chords can also be formed by a group of notes from a melody (broken chords), the use of intervals is to a point related to harmonies.

This subject hasn't been specifically investigated by me, but it does get dealt with in the Ludwig study (pages 127-132).

He has put the number of occurrences of intervals

in a table, that I would like to reproduce here. It takes an awful lot of time to set this up. In my study there are over 500 examples, while

you've got the Frank Zappa Guitar book and the Hal Leonard series at your disposal just as well. So I'm rather assuming that the Ludwig table is representative

for Zappa's composed diatonic music.

Intervals table.

This outcome concerns the lead melodies from the Frank Zappa songbook vol. I and the transcriptions in his own study (pages 218-259).

The titles are mentioned in the scores section from the left menu of this site. It's almost solely diatonic music, so no conclusions can be made

about intervals in Zappa's atonal music. The same goes for the guitar solos.

Minor and major seconds have been left out of the scope. Here Ludwig comments that they by far exceed the other intervals, as usual in most music.

Minor and major thirds are the next most common intervals in Western music, so it might be expected that they also occur frequently in Zappa's output.

What you can see happening is that all intervals within an octave are relatively common in his music. His fondness of fourths and, to a lesser degree, fifths,

can be recognized in this table. This subject is also coming by in my study in the Uncle meat (title song), Jazz from hell and Civilization phaze III

sections. Interval jumps over an octave are rare in both Zappa's music and music in general. An instance of a very large interval jump, a 12th, can be found

in the "Who are the brain police (1970)" examples from the Quaudiophiliac and Carnegie Hall sections from my study. A 10th can be

heard in bars 5-6 from my "Would you like a snack?" example.

Nicolas Slonimsky

In 1947 the conductor and composer Nicolas Slonimsky published his "Thesaurus of scales and melodic patterns". This book explores the possibilities

to form scales in a rather abstract and systematic manner. It goes ways beyond harmony books, that usually mention the seven diatonic scales and concentrate

upon major and minor. Hundreds of scales get constructed. This open approach must have appealed to Zappa, who contacted Slonimsky in 1981 and invited him to

perform some piano pieces during his 1981 tour. They became friends. The photo to the right comes from the http://www.slonimsky.net site.

The example included below is the start of the list. It begins by stacking equal intervals

till you get back at the initial note, one or more octaves higher. The octave can by subdivided as two tritones, three major thirds, four minor thirds,

six major seconds and twelve minor seconds. Three minor sixths form two octaves etc. Additional notes are brought in by for instance transposing the original notes

with a minor second, major second and a major third. In the example below the stacked tritones C-F#-C are the initial scale. Scale one has these notes

plus their transpositions with a minor second etc. The chords to the right are harmonizations with major triads, while the encircled numbers refer to dominant 7th

chords, included at the end of the book.

In 1947 the conductor and composer Nicolas Slonimsky published his "Thesaurus of scales and melodic patterns". This book explores the possibilities

to form scales in a rather abstract and systematic manner. It goes ways beyond harmony books, that usually mention the seven diatonic scales and concentrate

upon major and minor. Hundreds of scales get constructed. This open approach must have appealed to Zappa, who contacted Slonimsky in 1981 and invited him to

perform some piano pieces during his 1981 tour. They became friends. The photo to the right comes from the http://www.slonimsky.net site.

The example included below is the start of the list. It begins by stacking equal intervals

till you get back at the initial note, one or more octaves higher. The octave can by subdivided as two tritones, three major thirds, four minor thirds,

six major seconds and twelve minor seconds. Three minor sixths form two octaves etc. Additional notes are brought in by for instance transposing the original notes

with a minor second, major second and a major third. In the example below the stacked tritones C-F#-C are the initial scale. Scale one has these notes

plus their transpositions with a minor second etc. The chords to the right are harmonizations with major triads, while the encircled numbers refer to dominant 7th

chords, included at the end of the book.

Thesaurus of scales and melodic patterns, scales 1-3.

Slominsky is one of the persons who got interviewed for the Zappa! issue of Keyboard and Guitar player (cover to the left). About Zappa's

music he's saying:

"It has been my luck to see the emergence of this totally new type of music created out of the

recombination of dissonances between two tones, which are intervals, and a variety of separate

tonalities which are combined in various ways - that's the best definition I can give. It doesn't

contain quartertones or small intervals. Zappa sticks to 12 different notes and 11 intervals. What he does

with them in terms of organization is what is so far, far from traditional approaches. That's the

secret of his greatness. But, of course, he is very careful. He doesn't just throw things together

without any order or without a plan of what to do next. He's somebody completely new and completely

different. Zappa sticks to the classical type of music. He is a classicist and a contructionist [...].

Zappa puts musical sounds together and creates something new but not destructive of scales and intervals."

Slominsky is one of the persons who got interviewed for the Zappa! issue of Keyboard and Guitar player (cover to the left). About Zappa's

music he's saying:

"It has been my luck to see the emergence of this totally new type of music created out of the

recombination of dissonances between two tones, which are intervals, and a variety of separate

tonalities which are combined in various ways - that's the best definition I can give. It doesn't

contain quartertones or small intervals. Zappa sticks to 12 different notes and 11 intervals. What he does

with them in terms of organization is what is so far, far from traditional approaches. That's the

secret of his greatness. But, of course, he is very careful. He doesn't just throw things together

without any order or without a plan of what to do next. He's somebody completely new and completely

different. Zappa sticks to the classical type of music. He is a classicist and a contructionist [...].

Zappa puts musical sounds together and creates something new but not destructive of scales and intervals."

I guess this is more about "Drowning witch" than about "Bobby brown" as it comes to something completely new. Slominsky's right about

Zappa not being the intellectual type of avant-garde composer. What he didn't do was:

- come up with a composing method of his own, write musical theories or try to establish a school.

- design new musical instruments himself or try to mutate existing ones.

- come up with deviant chords and scales typical for his music, or compose with for instance quartertones.

Slominsky's is also right in saying that Zappa's basis could be called classical:

- 4/4 is the most common meter in his music.

- triads and 7th chords are the most common chords.

- most bars don't contain irregular groupings.

The introduction of the Thesaurus ends with Slominsky citing John Stuart

Mill: "I was seriously tormented by the thought of the exhaustibility of musical combinations.

The octave exists only of five tones and two semitones, which can be put

together in only a limited number of ways of which but a small proportion are

beautiful: most of these, it seemed to me, must have been already discovered,

and there could not be room for a long succession of Mozarts and Webers

to strike out, as these have done, entirely new surpassing rich veins of musical beauty."

Slominsky continues by saying: "The fears of John Stuart

Mill are unjustified. There are 479,001,600 possible combinations

of the 12 tones of the chromatic scale. With rhythmic variety added to

the unbounded universe of melodic patterns, there is no likelihood that new music

will die of internal starvation in the next 1000 years."

Rhythmic variations in music are unlimited and the note system supports

any rhythm for its n:m notation, the possibility of tuplets within

tuplets and to make tempo changes absolute by metronome numbers. Zappa fully

took advantage of this, briefly summarized in the Roxy and elsewhere section

of this study. He could do anything, but stayed within the following two boundaries:

- in case of sheet music, humans should be able to perform it.

- irregular rhythmic groupings should be functional.

The latter means that for instance you won't find a 21:27 figure is his

music. For the human ear such a relationship is too odd to be consciously

experienced. But 21:16 within a 4/4 environment is viable.

The subject of the number of possible chords has been investigated

by some mathematicians, of which I'm reproducing the results in chapter

V of my discussion with Brett Clement (see the left menu). The number of 479,001,600 Slominsky is giving here

is 12! or 12*11*10*9*8*7*6*5*4*3*2*1, but one could consider if one shouldn't better look at chord types by excluding inversions and transpositions.

Than the number still remains large, but more overseeable. I could use the outcome of the intervals table by Ludwig above, but

categorizing chords in Zappa's music is in my opinion undoable. One shouldn't only look at for instance keyboard or guitar chords by themselves (as songbooks

normally do). The only

neutral way is to take a full vertical cross section of everything you hear as is also done in analyzing orchestra sheet music. That is one should

include the bass parts and everything improvised as belonging to the chords too, because that's what you actually hear. In my opinion Zappa knew

no boundaries as it comes to chords. This doesn't mean that he used every possible chord type at least once, but that there's a reasonable probability of finding

them. Both the diatonic ones and the atonal ones.

The subject of the number of possible chords has been investigated

by some mathematicians, of which I'm reproducing the results in chapter

V of my discussion with Brett Clement (see the left menu). The number of 479,001,600 Slominsky is giving here

is 12! or 12*11*10*9*8*7*6*5*4*3*2*1, but one could consider if one shouldn't better look at chord types by excluding inversions and transpositions.

Than the number still remains large, but more overseeable. I could use the outcome of the intervals table by Ludwig above, but

categorizing chords in Zappa's music is in my opinion undoable. One shouldn't only look at for instance keyboard or guitar chords by themselves (as songbooks

normally do). The only

neutral way is to take a full vertical cross section of everything you hear as is also done in analyzing orchestra sheet music. That is one should

include the bass parts and everything improvised as belonging to the chords too, because that's what you actually hear. In my opinion Zappa knew

no boundaries as it comes to chords. This doesn't mean that he used every possible chord type at least once, but that there's a reasonable probability of finding

them. Both the diatonic ones and the atonal ones.

John Stuart Mill lived in the 19th century, when the possibility of non-diatonic music wasn't even considered. What he couldn't know, and perhaps

even Slominsky couldn't, is that pop music has shown that the market for music in 4/4 following the common chord patterns is unsatisfiable. You can fill

stadiums with it and get extremely rich and famous by it. It doesn't bother people if what an artist does sounds similar to what other artists have done before.

It's a pro rather than a con. There's a market for people as, say, Bartók, Schoenberg, Slonimsky and Zappa, but compared to mainstream pop-music it's marginal.

Beethoven

At the bottom of the Thing-Fish section of this study I'm briefly describing the music Zappa covered. There are also many citations of other composers

in his own compositions. Though he never openly expressed an interest in composers from before 1900, these composers do get covered and referred to as well.

Most notable is his exercise in getting Francesco Zappa's music on CD. Of course it was the latter's name that attracted Zappa's attention first, but it

is baroque music. Mozart is present on "Ahead of their time". There are two quotes about Beethoven included in this study, one in the quotes section

from the left menu and one in the L.S.O. section at "Strictly genteel". Neither are really positive. Beethoven can also be found as a bust on the

"We're only in it for the money" cover (outtake to the right). Citations of Beethoven in Zappa's own songs are only known from the bootleg circuit. Below are a

couple of screenshots from the www.zappateers.com and globalia.net sites.

At the bottom of the Thing-Fish section of this study I'm briefly describing the music Zappa covered. There are also many citations of other composers

in his own compositions. Though he never openly expressed an interest in composers from before 1900, these composers do get covered and referred to as well.

Most notable is his exercise in getting Francesco Zappa's music on CD. Of course it was the latter's name that attracted Zappa's attention first, but it

is baroque music. Mozart is present on "Ahead of their time". There are two quotes about Beethoven included in this study, one in the quotes section

from the left menu and one in the L.S.O. section at "Strictly genteel". Neither are really positive. Beethoven can also be found as a bust on the

"We're only in it for the money" cover (outtake to the right). Citations of Beethoven in Zappa's own songs are only known from the bootleg circuit. Below are a

couple of screenshots from the www.zappateers.com and globalia.net sites.

Quotations of Beethoven's 9th symphony.

As everybody knows Beethoven gradually grew deaf starting half-way his career, ending up completely deaf in the last decade of his life.

One might expect a deaf person to adhere to what he knows. One of the most fascinating phenomena in music history is that Beethoven didn't do that.

Instead he started to innovate music in such a degree that over a century many people thought that, at the end, he had become to deaf to compose. He simply

couldn't hear that what he wrote sometimes didn't sound right anymore. Today, with most people having become acquainted with modern music, this argument

is seldom heard. In fact Beethoven was way ahead of his time. Something for which, in my opinion, he still doesn't get the credit for he deserves.

Beethoven, Piano sonata opus 111, mvt. II, bars 98-99.

I would like to say some more about Beethoven regarding an example included in Brett Clement's response to me, where I'm pointing at the presence

of a chord, C-D-F-G, that in Brett's terminology might be called "cyclic". By cyclic he means a chord made up of stacking 5ths, as shown to the right (F-C-G-D).

Brett reacts: "How embarrassing! The D, F and G are chord tones of the V7 in C

major (the C is a dissonant pedal note). How does the use of a

dissonant chord in a functionally-tonal piece relate to my theory?"

Of course Beethoven follows traditional harmony and in traditional harmony

this chord gets interpreted as a dissonant passing chord (exactly as Brett says), which chord needs to be resolved by a triad upon C.

Which is formally also happening in opus 111. And of course I'm only trying to make some fun of his theory at this point.

His choice of words, however, is interesting, firmly stating that V7 in C is the only way to look at this example. Then you're missing something.

The C-D-F-G chord is being played for a whole bar two times during bars 96-99, being bars 97 and 99, standing as equal next to the C chord from

bars 96 and 98. Eventually it does resolve to C in bar 100. My interpretation is that Beethoven is doing more than just letting this chord resolve.

He also wants you to hear this chord as an independent chord, a chord by itself. Then it's not "V7 in C", but Csus2 and Csus4 combined.

This aspect is of interest in the context of Ruth Underwood saying sus2-chords attracted her to Zappa's music (coming by in the Zappa in New York section

of this study). It goes as far back as Beethoven and with modern composers as Debussy and Bartók it became normal to deal with such chords

as independent chords, that don't need to resolve.

I wouldn't be so sure of this if there weren't many more of such examples in Beethoven's late works. You can for instance hear accentuated dissonants

in his late string quartets. Next are three more examples from piano works.

Samples from Beethoven's late piano works.

- Piano sonata opus 111, Mvt. II, bars 106-119: another excerpt from the sonata from above, with Beethoven modulating from C to C minor.

Three notes are one by one getting altered, where a tremolo is creating dissonant chords. Most peculiar are bars 112-113, where there's

no melodic progression. Instead Beethoven is using a triple tremolo to get at a Bb 13th chord (without the C as 9th). In my opinion he's

quite intentionally letting such a large chord sound as an independent chord. Somewhat related to what I'm depicting above as Zappa using

a scale as a harmonic field. Moreover this 13th chord doesn't resolve. It's upper Ab continues as a tremolo, being chromatically led towards the C

from bars 115-116.

- Diabelli variations XXXII, bars 158-160. The second fuga from the variations series ends with a dissonant chord, to be played as heavily as possible:

fortissimo, with a pedal, sustained and with arpeggios. This chord is Ddim, already dissonant by itself, made extra dissonant by putting

an Eb pedal beneath it, being the root of its resolving chord Eb. Again Beethoven's intention of letting an uncommon chord - in this case

a sharp dissonant chord - sound as an independent chord comes out clear. It eventually does resolve in bar 162, but with so much weight upon

the dissonant chord this resolution becomes to sound as a mere formality.